To combat vaccine misinformation at home and around the globe, we must build trust.

Dr. Heidi J. Larson founded the Vaccine Confidence Project to monitor global public confidence in immunization programs by building an information surveillance system for early detection of public concerns around vaccines. “We don’t have a misinformation problem,” she says. “We have a trust problem.” The rise of social media as a news source, along with a general distrust of institutions, has exacerbated the problem. Scientists and global health specialists often speak in jargon that many people don’t understand, and vaccines are sold by large pharmaceutical companies, which generally rank very low in public trust.

In addressing the connection between vaccine hesitancy and preventable disease outbreaks, Dr. Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, observed that “public health is about trust.” “The way to do that,” he says, “is engagement with communities. Facts alone don’t make this happen. Building trust is an everyday action, and it requires understanding and respecting the concerns people have.”

Studies have found that one of the best ways to build trust in health interventions like vaccines is not by websites of facts and statistics, but by conversations with trusted members of a local community. This tends to vary based on the country and community. In the U.S., local pharmacists are seen as one of the most trusted sources. For example, UN Foundation partner Walgreens has more than 9,500 community pharmacy locations across the U.S. Its pharmacists work to get to know those in their communities, build relationships with customers, and answer their questions and concerns about medications and immunizations.

Eliminating Misconceptions Around Vaccines

Since 2013, Walgreens and the UN Foundation’s Shot@Life campaign have worked together through the Get a Shot. Give a Shot program to help provide more than 60 million lifesaving vaccines for children around the world, committing to providing a total of 100 million vaccines by 2024. This partnership reflects Walgreens’ commitment to educating and supporting not only the communities where their stores are located, but also the larger global community. This effort, combined with the ongoing vaccine delivery programs of UN agencies and other global health partners, will help continue to dispel vaccine myths, empower families, and save lives around the world.

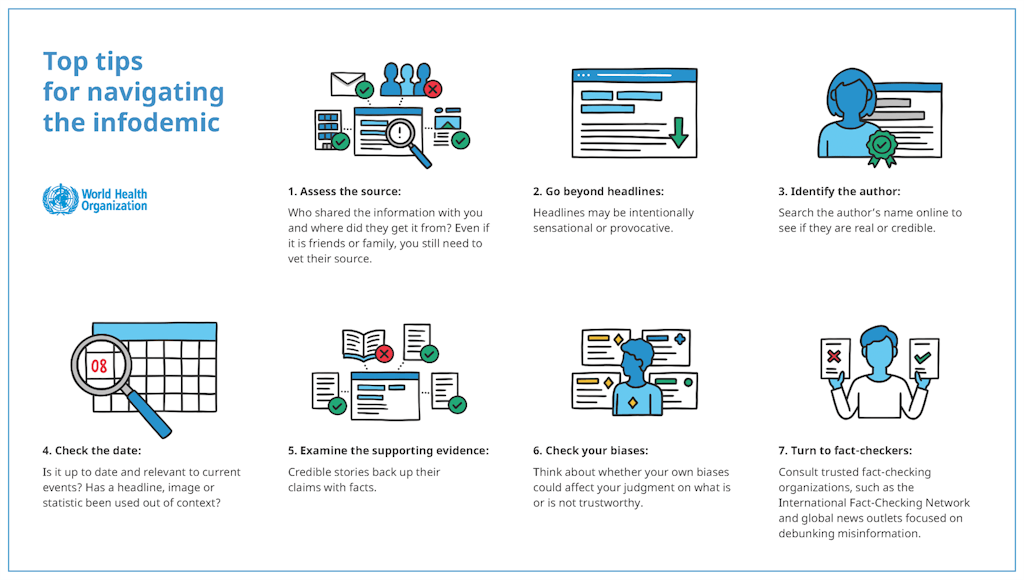

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation around vaccines has only gotten louder. The World Health Organization (WHO) is providing resources to help navigate what it calls the “infodemic” and is identifying misinformation online. In addition, the UN’s Verified initiative is calling on people around the world to become “information volunteers” and share UN-verified, science-based content about COVID-19. As scientists learn more about the virus and vaccines are introduced, the onus has become even stronger to rely on facts to keep families and communities safe and connected.

On the ground, global health organizations and UN agencies such as WHO and UNICEF work with teachers, religious leaders, community leaders, and local government officials as they design and implement new immunization programs. After all, these are the people who know their local context best: They have the power to help educate, dispel any fears, and improve the overall health of those in their communities. Similarly, countless front-line health workers spend years building relationships within communities so they can be trusted to help make recommendations for their patients and their patients’ children.

Despite these efforts — and the long-term positive impact of improved vaccine development, access, and distribution — many common misconceptions persist about vaccines and their efficacy. Here are three of the most frequently asked questions about vaccines.

Misconceptions: 3 Vaccine FAQs

Can a vaccine give someone the disease it’s supposed to prevent?

It’s not possible to get the disease from any vaccine made from an inactive or dead virus. Only those immunizations that are made from weakened strains of the virus, such as the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine, could make a child develop a mild form of the disease in rare cases. However, that mild form is almost always much less severe than if a child became infected with the disease-causing virus itself, and with the MMR vaccine, 97% of children are protected against all three viruses after the required doses. Because vaccines could cause problems for children with weakened immune systems, such as those with autoimmune disorders or those being treated for cancer, it’s important that others in the community get vaccinated to create herd immunity and help protect community members who cannot receive certain vaccines.

Why do we still need vaccines if rates of disease were already going down?

Improved access to routine medical care and improved quality of living in communities have made a tremendous impact on reducing disease. Vaccines, better nutrition, sanitation, access to clean water, and the development of antibiotics have all greatly reduced disease transmission.

However, declining rates of disease don’t mean the work is done: babies are born every year, and as a global community, we are never truly safe from a disease until it has been eradicated worldwide. The only disease that has been eradicated is smallpox, which was extinguished in 1980. Vaccines are the second greatest contribution to global child mortality reduction in the past 20 years, after clean water.

One strong example is the measles vaccine. In 1980, before widespread vaccination, measles caused more than 2 million deaths each year. Widespread measles immunization efforts resulted in a 73% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2018 worldwide. But recent data has shown this trend is reversing as case counts and measles-related deaths are rising globally once again. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many immunization campaigns were put on pause. In May 2020, more than half of surveyed countries reported moderate to severe disruptions of vaccination services due to the pandemic, putting 80 million children under the age of 1 at risk.

Why do children need to receive a vaccine for a disease that’s been eliminated?

An “eliminated” disease means transmission has stopped in a specific country or region, while an “eradicated” disease is one that has been extinguished on a global scale. Diseases that are rare or eliminated in the United States, such as measles and polio, still exist in other parts of the world, and an infectious disease anywhere is potentially a disease everywhere. Doctors continue to vaccinate against these diseases because it’s easy to come into contact with disease through travel — either Americans traveling abroad or people who are not fully immunized traveling to the United States.

Even though measles was declared eliminated from the U.S. in 2000, many states have reported outbreaks in recent years (elimination means that a disease has not been transmitted continuously for over a year, but it doesn’t mean there are no outbreaks). These cases were mostly among people who did not get vaccinated. Other preventable diseases that had recent outbreaks include whooping cough (pertussis) and mumps.

It’s safe to stop vaccinations for a particular disease only when that disease has been eradicated worldwide, as is the case only with smallpox.

Protecting Progress on Vaccines

The science supporting vaccines and the impact they have in global health is clear. The UN Foundation is committed to conveying fact-based information and working to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through our support of UN agencies such as WHO and UNICEF and global health partners like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Our Shot@Life campaign aims to ensure that children around the world have access to lifesaving vaccines. Through public education, grassroots advocacy, and fundraising, we strive to decrease vaccine-preventable childhood deaths and give every child a chance for a healthy life, no matter where they live.

Featured Photo: Raphael Pouget/UNICEF

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts