Off the coast of Panama, a sanctuary for marine life and ancestral wisdom is flourishing. Here, Duiren Wagua, a photographer and member of the Gunadule nation, documents how Indigenous communities like his are weathering the effects of climate change while taking action. His photos reveal what good environmental stewardship looks like — in spirit and in practice.

Duiren Wagua is a member of the Gunadule nation, an Indigenous archipelago off the coast of Panama. For the past century, the tribe has had full sovereignty and autonomy over 49 islands and surrounding waters. Since then, this territory — known as Guna Yala — has become the most biodiverse marine environment in the region.

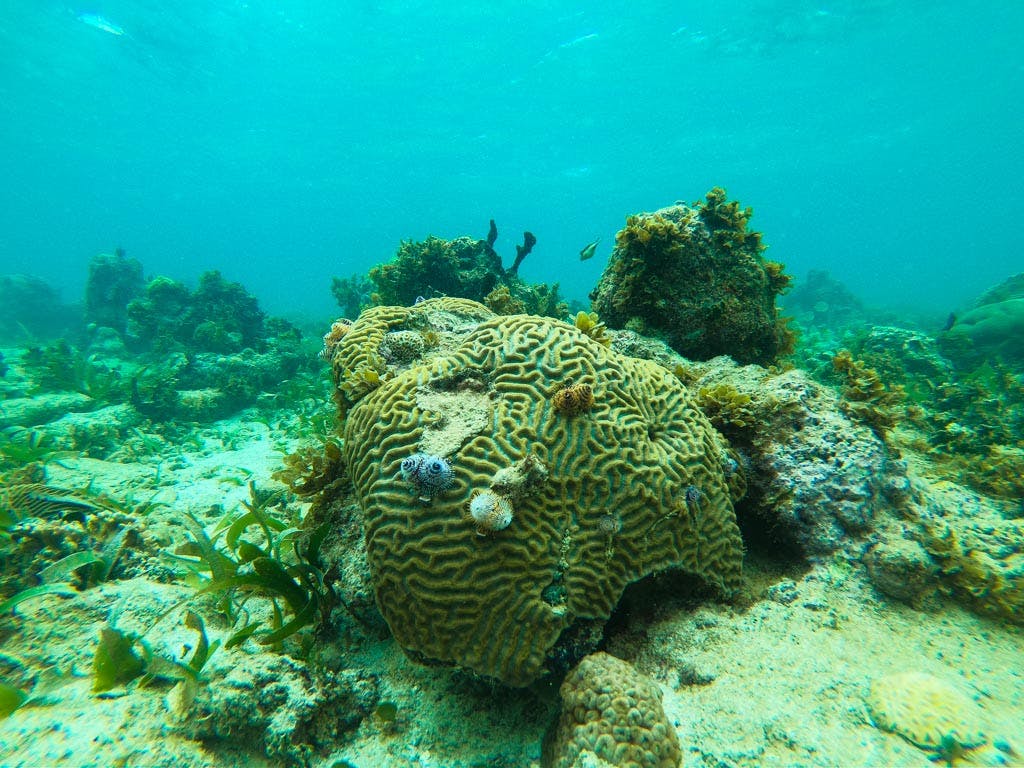

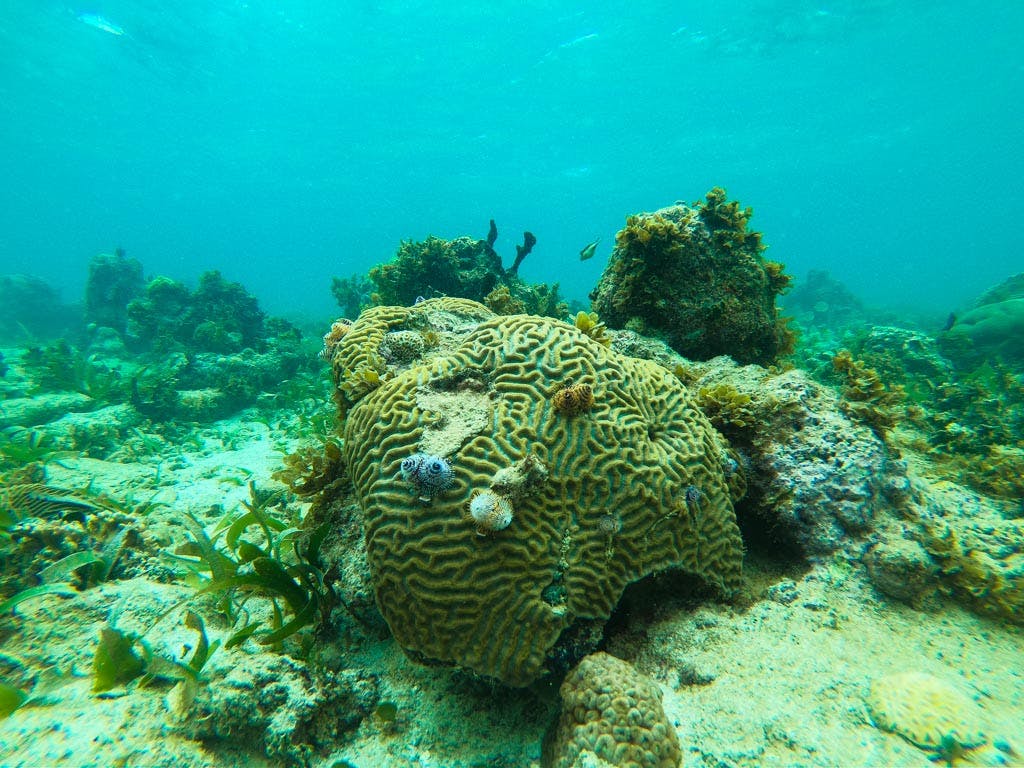

When it comes to environmental stewardship, the Gunadule have played a crucial role in protecting one of our planet’s most precious resources: its coral reefs. Today, more than 80% of Panama’s living coral reefs circle this Indigenous territory. This coral sanctuary has become even more precious in recent years; three-fourths of the world’s reefs have been bleached by ocean warming and acidification.

As a filmmaker and photographer, Duiren Wagua tells stories of his people, community, and ancestral life, as well as the environment they inhabit and the biodiversity they seek to protect. Photo: Duiren Wagua

Such wildlife and habitat loss has had devastating consequences for the environment. Though coral reefs make up less than 0.1% of the ocean’s surface, they harbor 37% of all marine species, according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). One billion people depend on these reef ecosystems for food, medicine, tourism, and natural protection from flooding and erosion.

“We have a recent relationship with the sea, with Muu Bil-li, the greatest grandmother,” Duiren says. “The coral reefs make up one of the most productive ecosystems in our Muu Bil-li. They also form natural barriers that protect the coastal areas and islands against high and intense waves.”

Through his photography, Duiren shares his community’s way of life with the wider world, as well as the water and wildlife that have shaped the Gunadules’ history and traditions. His images reveal how everyday life is inextricably connected to the landscape around them. The word “Gunadule” itself reflects this sacred relationship. Guna means “surface of land,” and dule translates to “people.” This connection includes how the community eats.

The corals in Guna Yala are among the most diverse in all of Panama. Photo: Duiren Wagua

“The ancient ones speak of Ised: taboos found in our legends that tell us about species we must not consume. To do so would take their spirit,” Duiren says. “They instruct us that we must not eat octopus, tortoise, shark.”

This, he explains, is how marine conservation is built into the Gunadule culture.

In 2020, the United Nations Foundation commissioned five Indigenous photographers, including Duiren, to document the local land, water, and wildlife across the Caribbean and show how climate change is threatening their future.

Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by the consequences of climate change. This is especially true for small island states, which are even more vulnerable to sea level rise and severe hurricanes — two of the most devastating consequences of climate change.

Gunadule men start the day with fishing. Photo: Duiren Wagua

That’s why embracing and elevating Indigenous voices is crucial for rethinking and reimagining how to distribute and manage natural resources and relate to the environment around us. The experience and ancestral wisdom of communities like Duiren’s offer important and often overlooked perspectives. According to National Geographic, Indigenous people protect 80% of global biodiversity despite making up less than 5% of the world’s population.

The Gunadule worldview, for example, is grounded in the concept of sumak kawsay (“living well”), which regards people as a part of nature, not apart from or above it. Like his ancestors, Duiren recognizes nature and its elements as relatives. It’s why the planet deserves as much respect, rights, and protection as the people who live here.

“Our ancestors’ relationship with our greatest grandmother was something that had to be learned,” Duiren says. “Our ancestors had to discover how to deal with the waves, currents, and corals.”

When it comes to taking climate action and moving forward, he says we should first look to the past.

“We must once again listen to our forebears, feel the cosmos, and return to being part of the biodiversity of the animals, minerals, and forests.”

Take Action

As humanity teeters on the brink of environmental catastrophe, people across the globe are stepping up and taking climate action in their own countries and communities.

Our Climate Is Our Future, a United Nations Foundation initiative, highlights the work of these unrelenting advocates and activists who are on the frontlines of the fight to protect our planet.

Stand with them.