I could never have imagined as a child growing up in rural India that the meals my grandparents cooked for me would eventually lead me to a career at the United Nations Foundation.

As a young girl, I lived with my grandparents in Edathua, a small village in Kerala, India. They cooked on a traditional wood-burning cookstove that produced thick plumes of indoor smoke. As a toddler, I often suffered from upper respiratory infections, likely due in part to the poor indoor air quality inside my grandparents’ home.

When I was four years old, my family moved from Edathua to Chicago. Both Edathua and Chicago are home to me, and life in both seemed ordinary growing up. But on a visit back to my grandparents’ home when I was 15, I noticed just how much black smoke came from their kitchen.

This was the first time I really looked at the polluting, inefficient cookstove that my grandparents used to prepare most of our meals. I remember being so intrigued by it that I decided to take this photo. Kerala is known as the land of coconut trees, and you can see in the photo I took that coconut husks and wood were my Aamachie’s (grandma’s) cooking fuels of choice; both are stored below the stove. You can also see the soot coating everything around the stove, including the pots and walls.

I asked my mom, who is a nurse, about the health effects of the black smoke I saw coming from the kitchen. She told me that my grandparents often suffered eye and respiratory conditions, more than likely due to a lifetime of exposure to indoor air pollution. This conversation opened my eyes to a global health issue that is too often overlooked.

Today, 3 billion people worldwide – almost 40% of the global population – rely on polluting, open fires or inefficient stoves to prepare their meals and heat their homes. These stoves burn using fuels like wood, charcoal, coal, animal dung, and kerosene. Without clean cooking technology and fuels, household stoves produce dangerous amounts of indoor (and outdoor) air pollution. Air pollution is the leading environmental health risk globally, and household air pollution contributes to a range of diseases including childhood pneumonia, heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer. Each year, household air pollution contributes to the premature deaths of close to 4 million people, which includes nearly half a million deaths per year in India. Nearly 60% of the population of India depend on polluting, open fires or inefficient stoves to cook their food, harming the country’s health, the climate, and the environment.

As for the environmental consequences of inefficient cookstoves and fuels, up to 25% of black carbon emissions – the second largest contributors to climate change – come from burning solid fuels for cooking and heating inside the home. Roughly 30% of wood harvested for fuel is not sustainable, leading to widespread forest degradation and worsening the effects of climate change as a result. Because of their unparalleled capacity to absorb and store carbon, forests are a crucial component for combating climate change, according to UN Environment.

While the health and environmental benefits of cleaner cooking technologies are what initially drew me to this field, I have also learned about the very real ways that women, communities, and refugees can benefit.

Because women and girls are often the main fuel-gatherers and food-preparers, they are disproportionately affected by indoor air pollution. Inefficient cookstoves don’t just harm their health. The amount of time spent gathering fuel and tending fires while cooking is time that could otherwise be used for school, work, play, or rest. This so-called “time poverty” only perpetuates gender inequality. Women and girls are also vulnerable to violence when gathering wood and other cooking fuels, leaving them to face the impossible choice between protecting their personal safety or feeding their families.

The consequences of this type of cooking are staggering, and the global community is working to find solutions. Last November, the World Health Organization (WHO) and partners convened the first-ever Global Conference on Air Pollution and Health. At this meeting, members from national and city governments, intergovernmental organizations, civil society, philanthropy, research, and academia came together to review progress on the global goal of mitigating diseases and costs to society due to exposure to air pollution.

The perpetual challenge of converting households to clean cooking technologies is that cooking is intimately intertwined with culture and tradition. My mother learned to cook from my grandmother, who in turn learned to cook from her mother. It is a profoundly personal and context-specific technique that is passed down from generation to generation. Asking someone to alter the way they prepare food requires significant behavior change.

In my grandparents’ case, after my parents left India to work abroad, they had enough money to buy my grandparents a new gas stove, hoping this would encourage them to stop using their old traditional wood stove. Even after my parents set up the gas stove and showed my grandparents how to use it, the wood stove was still their preferred way of cooking, and they would only use the gas stove for heating water or milk. Traditional stoves are often used because they are inexpensive and wood fuel can be gathered at no monetary cost. This makes it difficult to create clean cooking solutions that are financially and culturally acceptable for poor rural families, who bear the largest burden of household air pollution worldwide.

That’s where the Clean Cooking Alliance comes in. Housed by the United Nations Foundation, the Clean Cooking Alliance is working to create a thriving global market for clean and efficient household cooking solutions. The Government of India is investing in this work through a massive nationwide campaign to connect more than 80 million households to clean cooking gas. To date, over 60 million households have been connected to clean cooking gas under the Prime Minister’s initiative, Pradhan Mantri Ujjawala Yojana (PMUY). The Alliance is coordinating with multiple government agencies on product distribution, policy and planning, standards and testing, research, and South-South Cooperation. In partnership with both Shell Corporation and the Tata Trusts, the Alliance is implementing a campaign in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh to raise awareness of and demand for clean cooking solutions. The Alliance is also beginning to work with the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai and others to explore strategies that would help promote solar energy for cooking – a growing priority for the Government of India.

Today, over 20 years after I left India and moved to the U.S., I now devote my professional life to this issue as a member of the Clean Cooking Alliance in Washington, D.C. I feel fortunate to work for an organization tackling such an important and often overlooked global issue, one I first encountered inside my grandparents’ home as a young child.

Through my lived experience in India and the household air pollution research I conducted in rural Peru as a graduate student, I have seen firsthand the very real consequences of living in a home with severe household air pollution, like the chronic respiratory illnesses that plagued me as a child.

Clean cooking is integral to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by all UN member states in 2015. Reducing the health impacts of household air pollution is explicitly stated as part of SDG 3: to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being. Increasing access to clean fuels and technology is also a crucial part of SDG 7, which seeks to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. In fact, clean cooking is essential to 10 of the 17 global goals.

When it comes to the future of clean cooking, my time at the UN Foundation and the Clean Cooking Alliance has made me optimistic about our collective future. I am encouraged by recent advances in design, testing, and monitoring of clean cooking technologies; the compelling research on the health benefits of reducing smoke exposure; and the promising commercial business models that deliver cleaner and safer products more efficiently. I am honored to be working as part of the Clean Cooking Alliance on this very personal issue, and I am hopeful that the progress we have made will soon make it possible for cleaner stoves and fuels to reach the billions of people with harmful levels of smoke inside their homes.

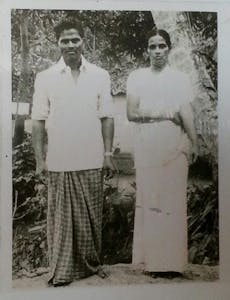

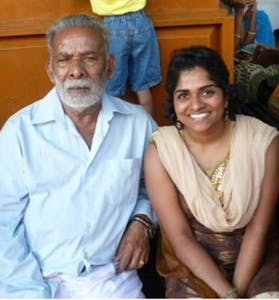

As I write this, I only have one surviving grandparent, but I often wonder if my grandparents’ lives would have been different had they known about the harmful effects that their cookstove was having on their health. Would they have been able to live longer, healthier lives than they were able to? When I asked my mom this question, she said that it is hard to tell if their lives would be any different because cooking with wood or coconut husk was the norm. It was acceptable and ordinary for your kitchen to be filled with smoke, and they were lucky that they had enough wood for cooking and enough food for eating. Having your kitchen filled with smoke was an accepted necessity of daily life for my Aamachie, my mother, and their family. This sentiment reminded me exactly why it is I am drawn to this issue – to help change what we see as acceptable and improve the quality of life for the billions of people, like my family in India, whose homes fill with smoke every time they cook.

Maria Jolly is an Environmental Health Associate for the Clean Cooking Alliance. To learn more, check out their website.

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts