Sonika Manandhar is an entrepreneur and Young Climate Advocate whose startup is tackling Nepal’s chronic air pollution problem, while marshaling a squad of climate ninjas and supporting women’s financial independence.

When she was 5 years old, Sonika Manandhar would accompany her father, a minibus driver in Kathmandu, Nepal, on his Saturday routes. Seeing how his livelihood thrived with the support of a government loan taught her an important life lesson early on.

“I saw the trajectory of my family, from microentrepreneurship to now owning shares in big buses,” she says. “It all comes down to finance: with it, you can really grow a business and the economic status of your family, but without it, there is nothing.”

Pioneering green vehicles

This is a lesson Sonika, now 31, has taken to heart as the co-founder and chief technology officer of Aloi, a fintech start-up that connects female electric bus drivers to low-interest financing. In the 1990s, around the time that Sonika was driving around with her father, Kathmandu became an early adopter of electric vehicles — known as “safa tempo” — introducing a fleet of about 700 units, which was then the largest number of battery-powered vehicles of any public transport sector in the world. Unlike the rest of public transportation in Nepal, most of these vehicles were being operated by female microentrepreneurs.

“I call these women ‘climate ninjas,’” laughs Sonika. “They are driving these electric minibuses without even knowing that they are helping tackle such a big issue as climate change.”

Debi Shrestha and Sonika Manandhar during World EV day. Photo: Aloi

The safa tempo were a boon to Kathmandu, reducing carbon emissions by thousands of kilograms a day in one of the most polluted cities in the world. However, the electric buses, which offered a unique solution to the pollution challenge, were a short-lived promise. They run on lithium ion batteries that cost nearly $10,000, a prohibitive obstacle for the female drivers who were unable to access funding from formal institutions. As a result, many of the buses are now sitting around in garages, rusting.

“These women have been working in the sector for 20, 30 years, but they are not trusted with formal forms of finance because they’re working in the informal sector,” says Sonika. “They can’t show lenders any credit history, or digital footprint, or proof of income.”

Bridging the trust deficit

Enter Aloi. Using her computer engineering background, Sonika and her team came up with a system in which digital tokens help bridge the trust gap between lenders and borrowers. Women would be able to obtain microloans from institutions in the form of these tokens, which can be accessed via SMS “from the smartest phone to the dumbest phone,” says Sonika, and also use them to obtain goods and services from participating vendors. Meanwhile, financial institutions are able to track where their funds are going and the kind of impact they’re making. Sonika is proud that her team has been able to negotiate interest rates of 1.33% — a far cry from the crippling 20% rates that their users were accustomed to facing.

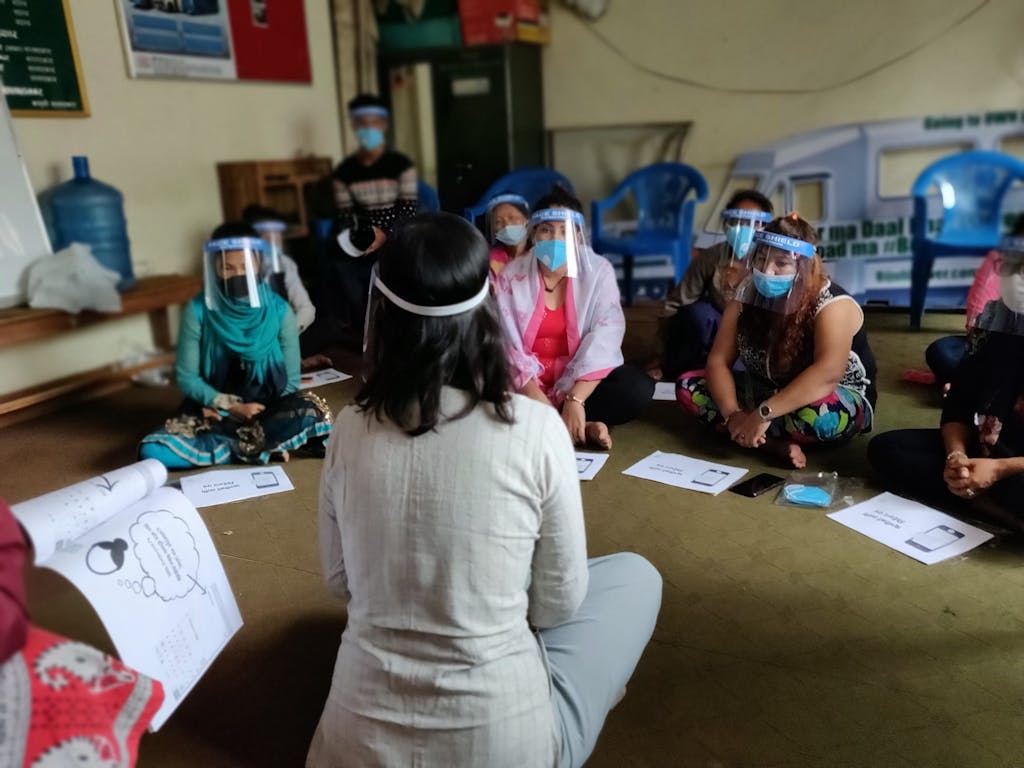

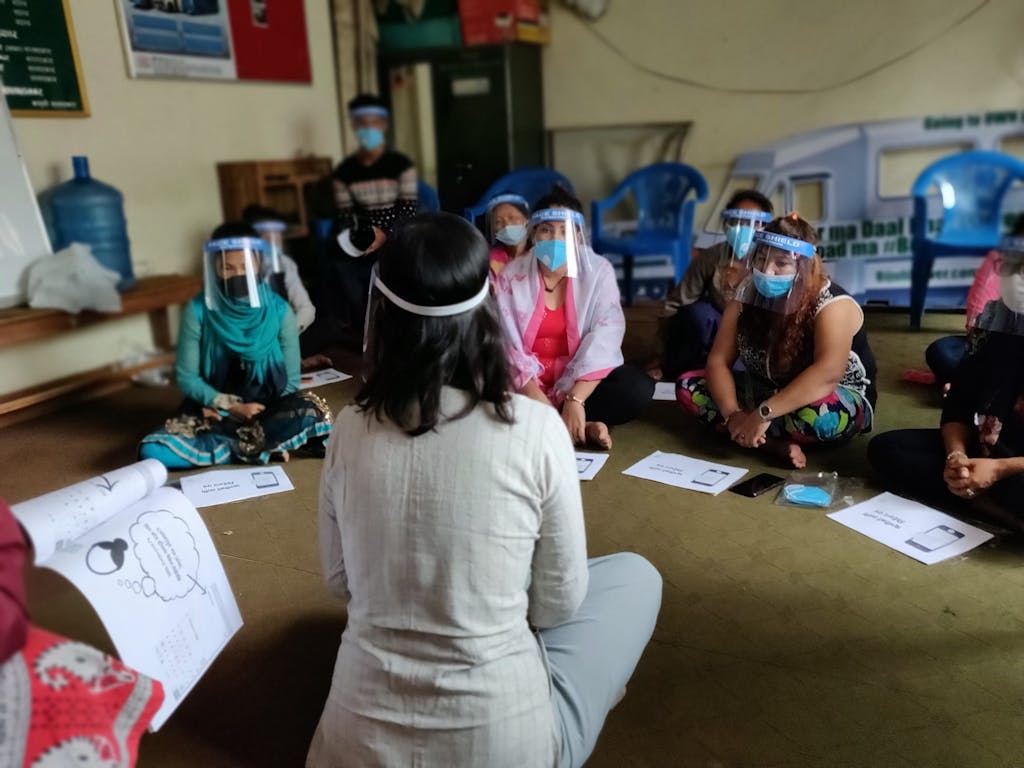

Sonika providing training on how to use tokens through the mobile phone to women EV drivers. Photo: Aloi

As a young woman, Sonika knows firsthand what it means to be the target of distrust. For example, when Aloi was started in 2019, she and her co-founder, Tiffany Tong — whom she met at an innovation challenge in Silicon Valley, a place that’s not the most hospitable to women in tech — had to work hard to persuade people that their idea would have impact and that they had the experience to execute it. Now, Sonika brushes off these experiences and looks to the optimism of like-minded peers such as the United Nations Foundation’s Young Climate Advocates network, a platform of over 800 young people in more than 100 countries. The network connects youths working on climate action around the world and provides a space for them to exchange resources and talk about what’s working — and not working — in their home countries.

“I really wanted to show the world that youth actually know the problem, and that we just don’t see it as a problem, but as an opportunity,” Sonika says. “Working in climate action is very tiring sometimes, both mentally and physically, so it’s important to surround yourself with people who align with your goal and vision.”

TAKE ACTION

As humanity sits on the brink of a climate disaster, everyday people are stepping up — finding solutions and addressing the climate crisis in their communities and countries.

Our Climate Is Our Future, a United Nations Foundation initiative, highlights the work of these unrelenting advocates and activists who are on the frontlines of the fight to protect our planet.

Stand with them.