If you look closely, you’ll see an “army of doers” rising around the world. The movement promotes a new vision — one we want to realize — that puts people at the center of justice to ensure that the future is fairer and more resilient for everyone. A new paper, “From Justice for the Few, to Justice for All,” explains what the movement toward people-centered justice could teach the world as it races toward the deadline for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Two of the co-authors sat down with Dynahlee Padilla-Vasquez for a conversation.

Thanks for taking time to share your perspectives on the paper, both of which are so unique. Kelechi, you’re an attorney living in Nigeria, and Maaike, you’re a thought leader on people-centered justice from the Netherlands, living in New York. What does people-centered justice mean to each of you?

Kelechi Achinonu | Nigerian lawyer, UN Foundation Next Generation Fellow for Justice: People-centered justice is user-friendly justice. It’s building institutions, frameworks, policies that people can actually connect with. So that anyone — a market woman in Nigeria or The Gambia, the policewoman, whoever it is — can basically understand what you’re solving these justice problems for. It doesn’t work if people cannot use it, people cannot access it, and people cannot understand it.

Maaike de Langen | Thought leader, Leads the Task Team of the Justice Action Coalition: People-centered justice requires us to take an honest look at what justice systems are, how they really work, and how we can improve them. Do justice actors and institutions actually help solve the problems that people face? Giving people options and empowering them to resolve their justice problems increases their resilience and reduces their vulnerability. Improving this ability to resolve and prevent justice problems can ultimately have a systemic impact.

Why are you choosing to write about people-centered justice now?

Kelechi: Right now, “justice” is a buzzword that everyone likes to use but not a lot of people are taking the time to do. By people, I mean countries, [government] ministers, people in power, people that have the capacity to do the things that need to be done for people. So that’s why I think that this is a good time to draw everybody’s attention to that: “‘Hey, we’re talking about this, but what exactly are we doing?’”

Maaike: People-centered justice is a shift away from talking only about the institutions and how we train more judges and how we build more courts. More and more countries and organizations are putting people at the center of justice, which I think is great progress. If you want to have responsive institutions and an effective justice system, you need to reach — and understand — people in all their diversity. So, this paper is also meant to mark the pivot that is happening in many countries and at the global level. We take stock of how far we have come over the past years: We have a growing movement, an army of doers that is increasingly connected and a practical agenda to increase justice. We then look ahead: What do we need to do and where do we need to go to really achieve this?

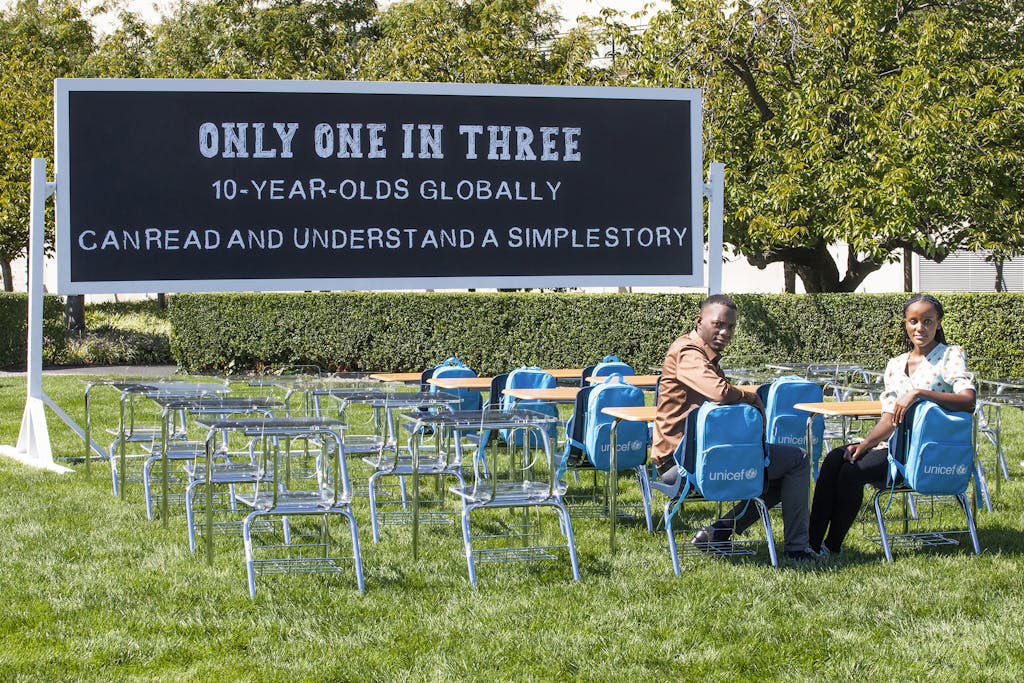

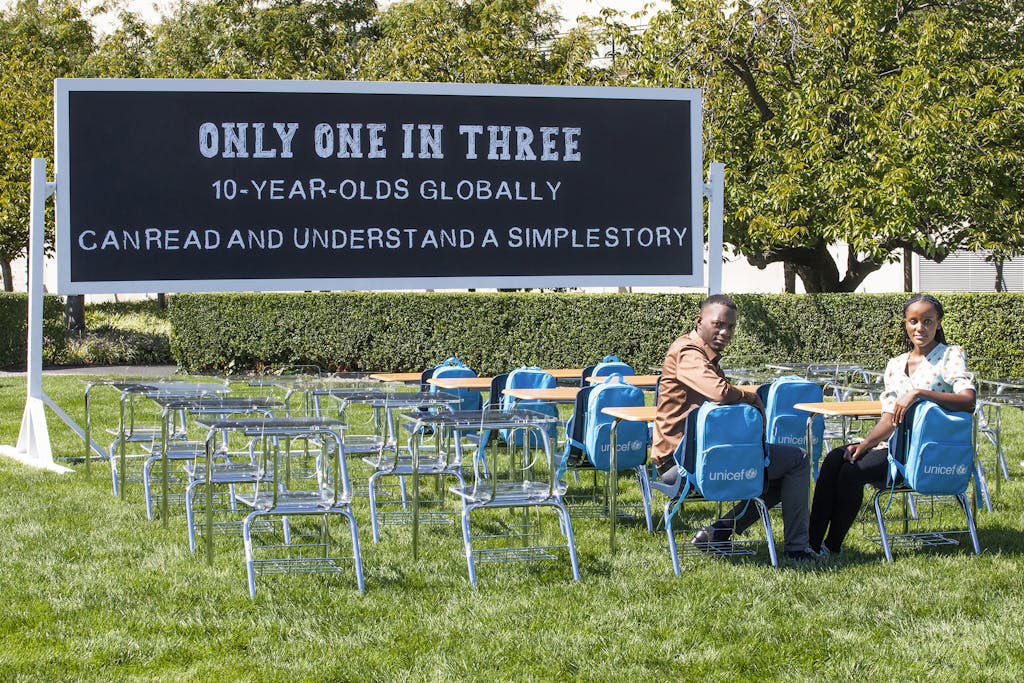

Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate and youth climate activist Davis Reuben Sekamwa visit the ‘Learning Crisis Classroom’ installation at United Nations Headquarters in New York. The ‘Learning Crisis Classroom’ represents the scale of children failing to learn critical foundational skills. Photo: Chris Farber/UNICEF via Getty Images

The Sustainable Development Goals are built on the premise of leaving no one behind. As the world lags behind on targets to achieve justice for all, who is being left behind the most?

Kelechi: The people. The people have been left behind. If it’s justice for all people — send the justice. You know that talking about justice is good for paparazzi and conversations, but then I think about the fact that we’re still having this conversation means something is wrong. The poor, the marginalized, the vulnerable, communities should feel that they’re getting justice in their countries right now — they should feel like they can confidently trust the system.

I also think that it’s about involving young people, right? I feel like at my age whatever decisions are being made right now are going to either make [or break] my future. The Pathfinders for Justice fellowship for instance, involves young people talking about justice problems, advocating for justice issues. It’s something I’ve seen work because as we are growing in our communities, we are closer to the people that are facing problems. We are also facing those problems. So having us involved in identifying problems and framing solutions has worked and is working well now.

Maaike: It’s actually the vast majority of people who are being left behind. We have estimated the global justice gap at 5.1 billion people, which is two-thirds of the world population who do not have meaningful access to justice. All these people are unable to stand up for their rights, resolve disputes peacefully, or access public services that they’re entitled to. In any context, the nondominant groups have the hardest time accessing justice. This can be women, children, people in situations of displacement, people with low literacy, ethnic minorities, and many other groups.

On the plus side, there are people working for justice and fairness in every country in the world. In the paper, we call them an “army of doers.” We believe that global goals and global meetings need to bring those people together and connect them, so they can inspire each other, share data and evidence, and learn from each other. People-centered justice is urgent in every country in the world: The mismatch between what the justice sector provides and what people and society need is really a universal issue. Systems have become so complex and so difficult to access that they have become distant and unpredictable, which is the exact opposite of justice.

There is a powerful “model recipe” outlined in the paper — six ingredients for building a high-ambition coalition for people-centered justice. Which ingredients are most essential?

Kelechi: We need data to actually make certain decisions, and I am a bit biased toward social entrepreneurship and investment. So I would say it’s investment in justice transformations, and financing, which really matters. And I think the next one will be political leadership and campaigning, which [builds] on bringing young people to the table.

Maaike: Well, I agree, using data and evidence is absolutely fundamental for people-centered justice. We also need global moral leadership, leaders who are willing to stand up for justice and fairness and be serious about achieving this in their own country, regionally, and globally. Global goals can serve to rally and inspire national justice leaders from all sectors, to set shared national or local goals and to co-create strategies to achieve them.

Asmita Chadotara, manager of the Women Reception Centre, addresses attendees at UJAVANI, a meeting on positive social norms, innovative practices and solutions, organized by UNICEF and local partners. Photo: Vinay Panjwani/UNICEF

What do you think will be the most significant challenge in achieving people-centered justice?

Kelechi: People-centered justice should move from just being a conversation to being an action. I feel like we’re still talking about it around the world and [especially heading into] the SDG Summit and afterward. But I think the difference should be what happens with all the talk. Therefore, it should move from just being a conversation that people want to have to a situation where people are acting on it. I would like leaders to come together to say “‘the last time we had the conversation, this was where we were. But now this is where we are.’” This would serve as evidence, showing that people now have access to justice or people are enjoying access to justice.

Maaike: Summits are by definition people talking to each other, and the SDG Summit will be no different. But are the conversations meaningful? Are they grounded in what’s really happening and what people are experiencing? Are they relevant to what people are trying to change? Can multilateralism be about bringing the people who are doing this together to learn from each other and improve together? It’s not about intergovernmental processes at the UN. It’s about networks. It’s about including people who are doing the work and inspiring and enabling them to make progress. The most significant challenge that I see is when people don’t believe that change is possible. The systems can change, they need to change, and we can change them. That’s true for the justice system and for the multilateral system as well. We discuss both in the paper.

Something we like to call the postscript: What would be one key idea you want people to take away from this report?

Kelechi: As a young person, I think there should be an opportunity to have young people more involved in the right stage of the conversations. We don’t want to have to play catch-up with what’s going on since we’re part of the community, part of society, part of countries. We know what’s going on. Bring us to the table.

Maaike: I absolutely agree that it’s very important to bring young people to the table in all their diversity. And that it’s important to build high-ambition coalitions that bring together civil society organizations and the justice defenders who are fighting for justice, the social entrepreneurs who are finding new solutions, the government, and the institutions and civil servants who are shaping the justice sector. A great example of this in practice is the Justice Action Coalition; it brings such diverse groups together around a practical agenda to achieve equal access to justice for all.

Thank you. We really appreciate this. Thank you, again, for this fruitful conversation.

Dive Deeper

Explore more insights on the high-ambition movement for people-centered justice.