In Nigeria, children of poor households are forced to quit school and support their families as COVID-19 leaves their parents jobless. It’s just one finding of an education study by the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa, an Abuja-based think tank and a member of the Southern Voice network of research organizations.

In Abuja, 14-year-old Faith no longer attends school because her family can’t afford it anymore. Instead, she now sells peanuts alone on the street, with her mother constantly fearing for her safety. Faith is an astute student whose teacher describes her as one of her best. She dreams of becoming a doctor one day.

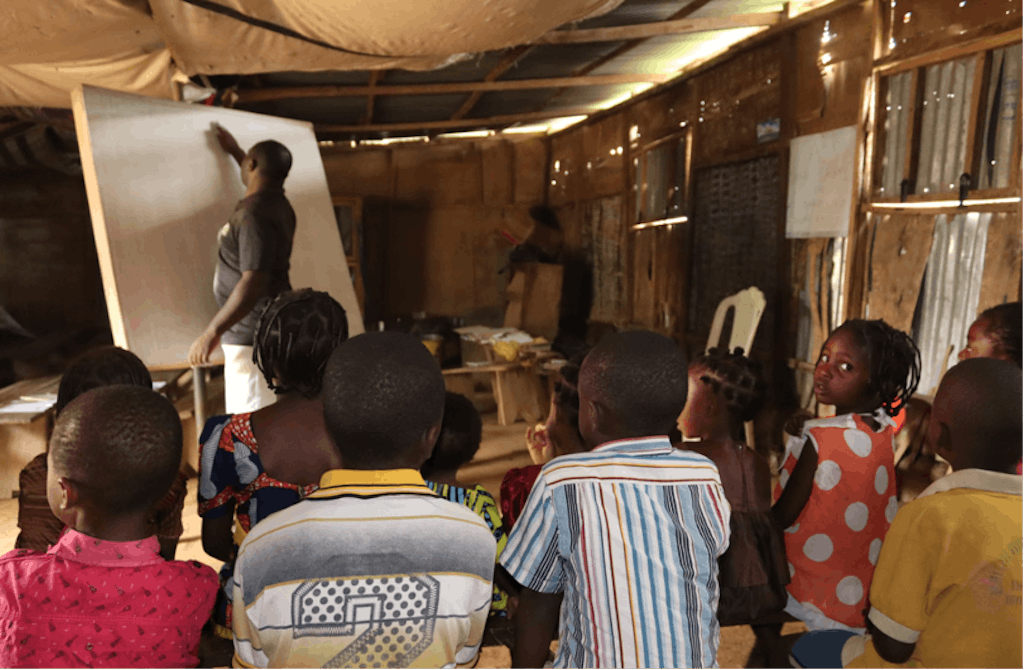

As one of the team members conducting a two-month study on education in Nigeria at the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA), I met Faith and her mother at a gathering of teachers and low-income parents and children. Women in the room sobbed quietly, one after the other, as they told me about their waning ability to bear the costs of basic education for their children since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The crisis has forced their children to take on work, such as selling food, to supplement already scarce earnings. The gravity of this problem dawned on me: It defies the powerful maternal resolve for the protection and advancement of a child.

There are easily millions of stories just like Faith’s across Nigeria, and millions of children who no longer have access to schooling. More than ever, the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (quality education) is in peril in this country. While schools across the country are reopening, many children whose parents may have lost jobs as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown won’t be going back to class in a country with an educational system that was already struggling. The pandemic has increased poverty in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation and one of its most unequal. And it has weakened already low demand for — and access to — quality education.

We launched our research project in August 2020. The aims were to explore the diminished demand of parents seeking education for their children and to study methods to mitigate and restore the learning losses of the past months. To begin to tackle this problem, CSEA selected 73 private schools in Abuja and paid for underprivileged children at these schools to receive supplementary teaching to help fill the gap.

Unemployed parents, working children

While distributing questionnaires to parents at one of the schools, I met Emmanuel, a 32-year-old former security guard. His three children no longer attend school. When Emmanuel lost his job during the lockdown, he had to send them back to his rural hometown. Since then, his children have been working on his father’s cassava vegetable farm. Hopes of them returning to the city and to school are bleak.

“Things were bad before COVID-19,” he said. “Now, things are so bad that I am hardly ever sure of my next meal. I have been living with a friend. I remained in the city, while my family returned home, so that, with any luck, I can find another job here. So far, my chances are not looking very good. Things are terribly difficult all-around at the moment.”

I then asked him if he was worried that his children, aged 6 to 11 years, can no longer attend school.

“I am very worried,” Emmanuel said. “There is very little I can do about the situation, unfortunately. For now, they have to work on the farm so that they can eat.”

Just like Emmanuel, nearly half of Nigerians currently live in extreme poverty. And just like him, most of them work in the country’s unregulated economy.

COVID-19 shook the livelihoods of people in the informal sector to the core. These people now earn significantly less than they had been earning or have been completely shut out of the labor sector. Informal sector workers typically earn their wages on a day-to-day basis. As such, any sustained drop in income will quickly limit their spending to only the most essential needs. Unfortunately, in the case of the extremely poor, education does not fall under that category.

Private vs. public schools

Paradoxically, when poor families send their children back to school, it is not to the government-owned schools, where education is free. I asked a group of administrators of the low-cost private schools selected for our study why this was the case. Their response was unanimous: “Many of these parents prefer our schools.” They explained that these parents prefer private schools for several reasons, including distance, quality, and the additional expenses often incurred at public schools.

That’s because, first, the available government school is usually not close, and the daily commute becomes an exorbitant cost in itself. Second, parents are wary of the quality of teaching in these often-crowded public schools; they have more confidence in the teacher-to-student ratio of private schools. And finally, public schools charge additional fees that can surmount the overall costs of low-cost private options. Yet, private schools generate their revenue solely from student enrollment fees, and they too have suffered with pandemic closures and reduced numbers of returning students, affecting their ability to operate effectively. The current requirements for hand-washing stations, face masks, and thermometers, as well as the challenge of achieving social distancing within limited physical spaces, present additional financial problems.

These stories are initial snapshots from our education study. As the pandemic continues to unfold, we want to develop practical, sustainable ways to address the challenges that low-income Nigerian families are facing. COVID-19 has shined a light on the intertwined problems of growing poverty and widening learning gaps in the country. As we continue to learn from these families’ stories, we hope that they may lead to empathy-driven action by policymakers for a society that children like Faith and parents like Emmanuel deserve.

Obinna Obiwulu is a writer and documentary filmmaker. His work focuses on development issues in sub-Saharan Africa and developing economies, and the subjects of his pieces are often economically disadvantaged and other vulnerable groups. As a communications consultant for the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa, he has worked extensively with internally displaced persons and impoverished households in Nigeria on a number of projects.

This story was provided by Southern Voice, a network of think tanks in Africa, Latin America, and Asia that amplifies local data and research in support of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The UN Foundation partners with Southern Voice to highlight local SDG stories from around the world.

Featured Photo: Obinna Obiwulu

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts