Besides leading the global fight against COVID-19, the World Health Organization is also investing time and resources to tackle the rapid spread of misinformation, rumors, and conspiracy theories about the virus.

Soon after the world started getting used to the terms “coronavirus” and “COVID-19,” the World Health Organization (WHO) coined another word: “infodemic” — an overabundance of information and the rapid spread of misleading or fabricated news, images, and videos. Like the virus, it is highly contagious and grows exponentially. It also complicates COVID-19 pandemic response efforts.

“We’re not just battling the virus,” said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. “We’re also battling the trolls and conspiracy theorists that push misinformation and undermine the outbreak response.”

Proliferating misinformation — even when the content is, in a best-case scenario, harmless — can have serious and even social and lethal health ramifications in the context of a global pandemic. In some countries, rumors about impending food scarcity prompted people to stockpile supplies early on in the epidemic and caused actual shortages. In the United States, an Arizona man died after ingesting a fish tank cleaning product containing chloroquine after hearing President Donald Trump tout a related drug, hydroxychloroquine, as a possible COVID-19 treatment. In Iran, hundreds died after drinking methanol alcohol that social media messages said had cured others of the coronavirus. This is the kind of dangerous misinformation that WHO is most worried about.

Even as the world is laser-focused on the search for a safe, effective vaccine, misinformation continues to spread about immunization as well. Health experts in Germany are concerned that the country’s anti-vaccination movement may deter many people from getting immunized when a safe vaccine becomes available. A recent study that examined the vaccination views of 100 million Facebook users globally found that while the pro-vaccination camp (6.9 million people) outnumbered those against vaccination (4.2 million), the anti-vaccine group was less isolated and had more interaction with the individuals (by far the largest group, at 74.1 million) who are undecided about vaccination. These “swing vaxxers” are important to target and get on board with lifesaving vaccination.

To learn more about how WHO is taking on the infodemic fight, the United Nations Foundation caught up with Tim Nguyen on the sidelines of the world’s first infodemiology conference, which brought together world experts to discuss the developing science of managing infodemics. Nguyen’s team manages the Information Network for Epidemics (EPI-WIN), which is leading WHO work on managing infodemics.

COMBING THROUGH THE WEB OF MISINFORMATION

“Infodemics have already happened in one way or another in past epidemics, but what’s happening right now is something of a global scale, where people are connected through different means and share information more quickly,” Nguyen said. “This has created a new situation where we are rethinking and reshaping our approach to managing infodemics in emergencies.”

According to a recent study evaluating English-language misinformation, the largest category of posts labeled as false or misleading by fact-checkers was content that deliberately challenged or questioned policies and actions of public officials, governments, and international institutions such as the United Nations and WHO.

One flagrant example of this is “Plandemic,” a 26-minute conspiracy theory video that falsely accuses Dr. Anthony Fauci, the leading infectious disease expert in the United States, of manufacturing the virus and sending it to China. The same video falsely claims that wearing masks will lead to self-infection. More than 8 million people watched the video across social media before it was taken down.

Such content can erode public trust in the very organizations leading the fight against COVID-19. To remind the public of the primacy of science, WHO first pinpoints what kind of misinformation is floating out there and then responds with its own evidence-based guidance. The wider United Nations community has been helping amplify this information through its own anti-misinformation initiative Verified. For example, the initiative’s “Pause. Take care before you share” campaign encourages people to take time to verify sources before deciding whether to share any content online.

WHO has also been working closely with social media and tech companies to help curb some of the misinformation spreading on their platforms. In February, officials from the health agency met at Facebook’s headquarters about how to promote accurate health information about COVID-19. Now, WHO is working with more than 50 digital companies and social media platforms including TikTok, Google, Viber, WhatsApp, and YouTube to ensure that science-based health messages from the organization or other official sources appear first when people search for information related to COVID-19. Even the dating app Tinder now features WHO health reminders, because social distancing is still appropriate during a date.

SOCIAL LISTENING WITH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

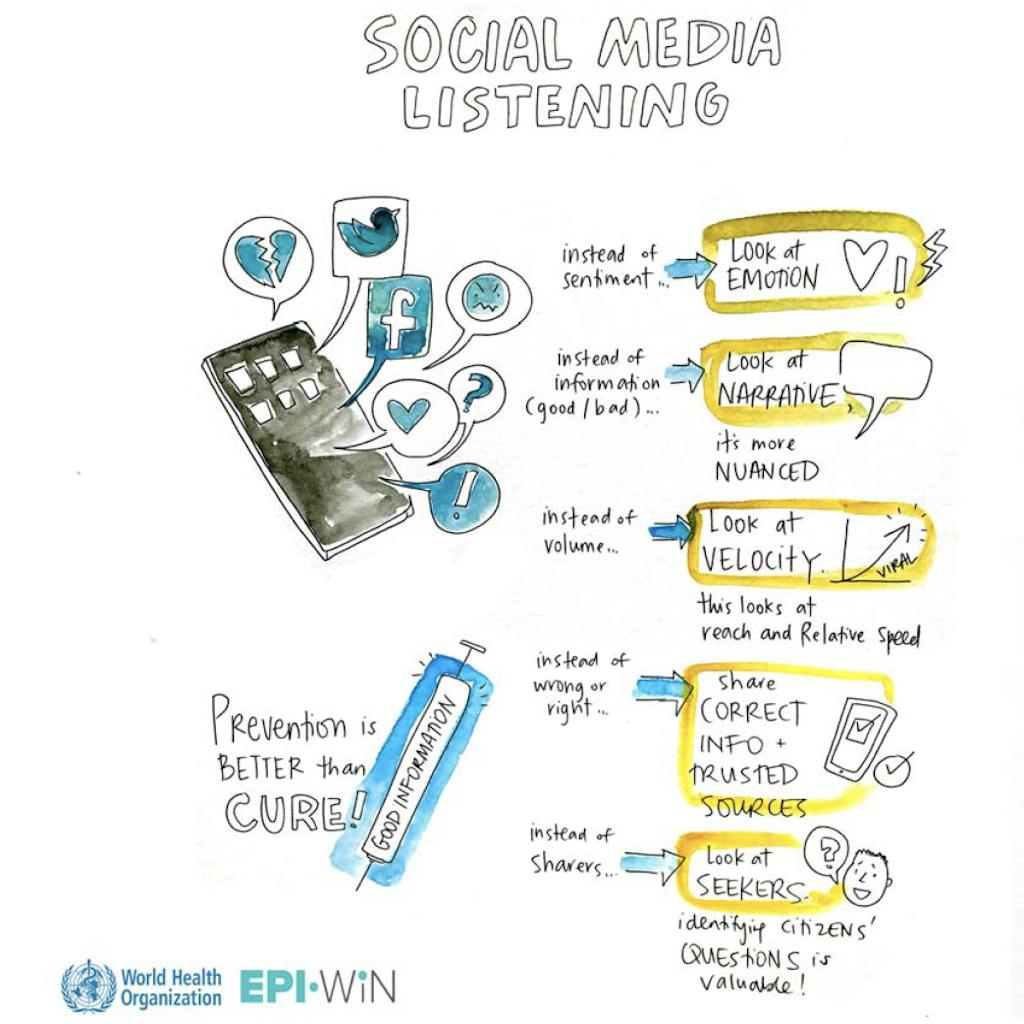

“Countering fake news or rumors is actually only responding or mitigating when it’s too late,” said Nguyen. “What we’ve put in place in the beginning of the pandemic is what we call a social listening approach.”

WHO is working with an analytics company to incorporate social listening into its public health messaging development — a first for the organization.

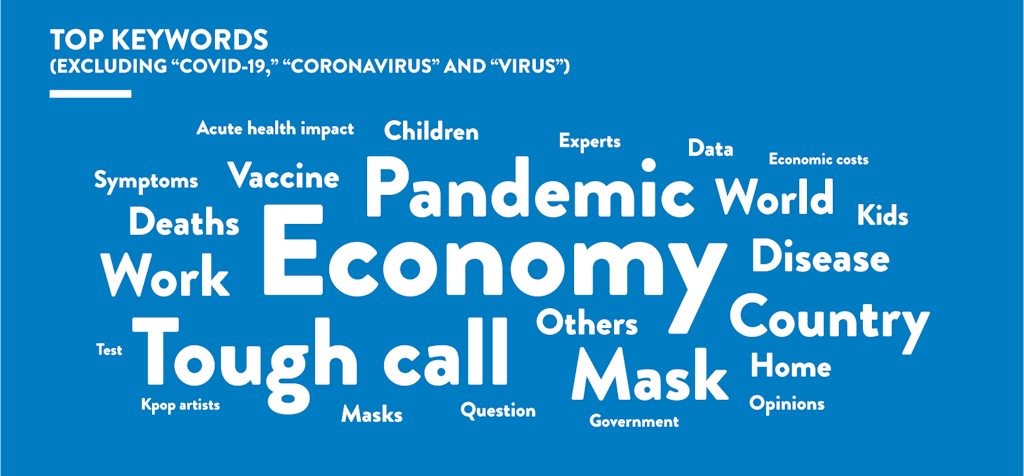

Each week, the company reviews 1.6 million pieces of information on various social media platforms, then uses machine learning to conduct searches based on a newly developed public health taxonomy to categorize information into four topics: the cause, the illness, the interventions, and the treatment. This helps WHO track public health topics that are gaining popularity and develop and tailor health messages in a timely way. Examples include “How does a pandemic end?” and “How do we know when we have a second wave of the virus?”

Machine learning also provides insights into what kinds of emotions users are experiencing. Instead of simply dividing the data by type of sentiment (positive, neutral, negative), language analytics can shed light on anxiety, sadness, denial, acceptance, and other emotions expressed in social media posts. This level of detail allows WHO to develop an effective offensive strategy and assuage the public’s concerns before misinformation can gain steam.

“What we’ve learned now, after two and a half months of doing this kind of analysis, is that there are recurring themes and topics that are coming back over and over again,” Nguyen said. “What that means to us is that we need to re-push information at different times. People may not understand it the first time when we push it, but when the questions and issues come up later, it means it’s time to push it out again.”

Not everyone has access to social media or the internet, but they remain just as prone as anyone else to being exposed to misinformation. To overcome this digital gap, WHO is working with colleagues from the UN Global Pulse initiative, which uses artificial intelligence and big data to tackle development and humanitarian issues and to apply social listening to countries where radio is a popular medium of information.

In Uganda, for example, more than half of households rely on radio for their news, and thousands of Ugandans call into local programs every day to talk about issues from the most mundane to serious topics such as health care. The Kampala branch of UN Global Pulse uses an automated speech recognition tool powered by artificial intelligence to translate the radio recordings from the local dialect into digital English text. The initiative was featured in the UN Foundation’s Innovation in Action series last year, showcasing how the UN is leveraging innovation and fresh thinking to address the world’s most pressing challenges.

The UN Global Pulse team is now using the tool to identify COVID-related language in Uganda and any misinformation that local communities are spreading. The team found that local communities were promoting witchcraft and herbs as COVID-19 cures; there were even rumors circulating about a vaccine being manufactured in Uganda. This kind of data is invaluable for organizations such as WHO to inform their messaging and guidance development. WHO is working with the UN to scale up and pilot this project for two additional countries in sub-Saharan Africa and two in Southeast Asia.

“You need to have a certain degree of good information out there to reach populations so that they are inoculated and not susceptible to fake news or disinformation,” Nguyen said. “We need to vaccinate 30% of the population with “good information,” in order to promote evidence-based advice and guidance.”

That’s where the local community becomes especially important in helping to amplify WHO’s messaging.

INCORPORATING COMMUNITY VOICES

Since much misinformation originates in communities and can spread in private messaging and conversations among friends and families, WHO encourages individuals to fact-check their loved ones when necessary. They’ve created a dedicated page of “Mythbusters,” featuring fact-based answers to the most common misconceptions about COVID-19, including: whether shoes can spread the virus (very low likelihood), if hot baths can keep the new coronavirus at bay (no, and you may get burned), and if hand dryers can kill the virus (no, they don’t).

While WHO is accustomed to working with health ministries and other government bodies and officials to develop and amplify public health messaging, Nguyen said that in a crisis of the magnitude of COVID-19, a whole-of-society approach is necessary to make sure all communities are reached. For example, instead of a top-down strategy, WHO works with specific groups such as youths, journalists, and faith-based organizations to co-develop guidance that is tailored to each context and community. These groups serve as amplifiers, transmitting accurate health information to people organically.

Nguyen noted that at the global level, information needs can be very different. “Let’s take the hand-washing guidance, for example. It’s important and there’s a global recommendation for how long and the way you need to do it,” he said, “but let’s also be honest. There are certain parts of the world where it’s not possible to do it as recommended.”

Community leaders can help tailor hygiene guidance in contexts where there may not be enough water sources or soap to properly wash hands, or in cramped conditions where social distancing may seem nearly impossible. Revised guidelines co-developed by WHO and faith leaders include replacing greetings of physical contact with a simple eye contact and bow; encouraging worshippers to complete ritual ablutions at home instead of at the place of worship; and even offering tips during painful situations such as how to bury loved ones while abiding by COVID-19 restrictions.

“It’s important to work with these amplification groups that understand the people they care for much better than we do,” Nguyen said. “We’re co-developing guidance with individuals who are directly affected and can help us implement a certain practice that leads to behavior change.”

A new UN alliance to fight the the infodemic — comprising WHO, UNESCO, the International Telecommunication Union, and UN Global Pulse — recently received just over $4.5 million from the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund to scale its community amplifier work, social listening initiative, and other projects including the creation of a centralized fact-checking and misinformation center to provide countries with tools to address the infodemic. On June 29, WHO also organized the world’s first infodemiology conference, which brought together scientists from diverse backgrounds to focus on the issue systematically and brainstorm science-based ways to better manage it.

“We have physicists, mathematicians, sitting with epidemiologists, with social scientists to discuss evidence-based approaches to manage the infodemic,” Nguyen said. “All of these scientific fields have their own schools of thoughts, their frames, how they do research, so it’s interesting how one perspective can help fertilize the other.”

While a vaccine for COVID-19 is not ready yet, WHO’s proactive steps are helping to neutralize the infodemic of misinformation.

“To tackle this infodemic, we need to do things differently than we have in the past,” Nguyen said. “Thanks to the leadership of Dr. Tedros, we are increasingly open to innovation and to rethink the way that we are doing things.”

HOW YOU CAN HELP FIGHT THE INFODEMIC

Have you seen rumors, conspiracy theories, and misinformation about COVID-19 floating around in your networks? We have, too. That’s part of the reason we launched the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund, the first and largest contributor of flexible funding to support WHO’s global pandemic response, including pushing back against the infodemic.

So far, more than half a million people from over 100 countries have donated. Every dollar makes an impact. Join our solidarity movement by donating to the global response to COVID-19.

You can learn more about WHO’s life-saving work around the world here, and find details of how funds are used to support COVID-19 efforts here.

Featured Illustration: Sam Bradd/WHO

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts