In Somalia, there are some days when the sky suddenly darkens as hundreds of millions of hungry desert locusts descend over the country’s crops.

This year’s locust outbreak is Somalia’s worst in 25 years, threatening the food supply and prompting the government to declare a national emergency in February. The infestation was exacerbated by heavy floods that have displaced half a million people and created an ideal breeding ground for the locusts

To that nightmare scenario, add a pandemic. A pandemic in a country already fighting serious threats on many fronts, such as terrorist groups that control large parts of rural areas, and widespread corruption.

Despite these challenges, the World Health Organization’s country representative is resolute.

“We can only end this pandemic if we can end it in settings like Somalia,” said Dr. Mamunur Rahman Malik.

A FRAGILE HEALTH SYSTEM

Somalia ranks 194th out of 195 countries on the Global Health Security Index (ahead of only Equatorial Guinea), its health systems decimated by decades of civil war. While the global standard for health care workers is 25 per 100,000 people, Somalia has only two health care workers per 100,000 people. With only 15 intensive care beds for a population of more than 15 million, it is listed among the least prepared countries in the world to detect and report epidemics or to execute a rapid response that might mitigate further spread of disease.

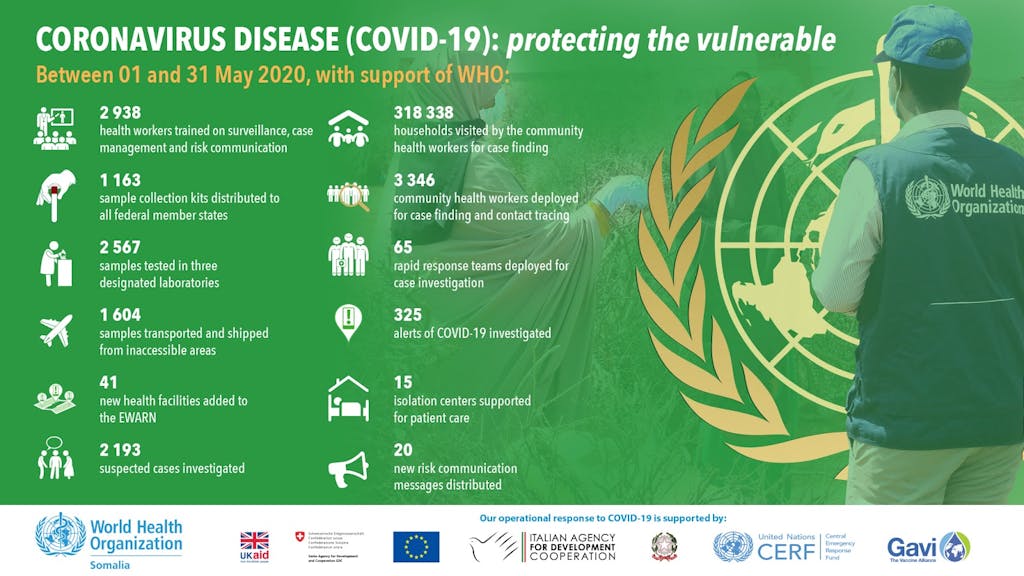

In January, WHO began pre-positioning enough personal protective equipment in Somalia to treat 500 patients and organizing trainings for health care workers. The local team quickly took nasopharyngeal swabs from four Somali students returning from China and sent them to the Kenya Medical Research Institute for testing. One of the results, from a 26-year-old male, came back positive on March 16: the country’s first official case of the virus.

More than 150 additional samples from around the country were sent to Kenya to be tested, while the WHO team began building local testing capacity. Two virologists were brought in from Ethiopia on UN special flights to provide expertise and help set up the facilities. The UN Humanitarian Air Service (operated by the UN World Food Programme) flew in molecular testing machines, procured by WHO, from Nairobi to the new testing locations. The UN Population Fund provided a biosafety cabinet and extraction kit machine, which is used to examine viral genetic material from the swabs.

In an unprecedented feat, WHO Somalia managed to set up molecular testing labs across the country by April 30: one each in Mogadishu, Garowe, and Hargeisa.

STEPPING IN FOR THE HEALTH MINISTRY

Another challenge unfolded in the Somali capital, Mogadishu. Only days after the first cases of COVID-19 were announced, 10 senior officials and staff from the Ministry of Health were arrested on corruption charges, and the prime minister’s office assumed control of the government-led response. With the Health Ministry under scrutiny, the WHO Somalia team assumed an even larger role, leading the charge against COVID-19.

Communicating the threat to the Somali population was critical. The WHO Somalia office drafted and translated COVID-19 awareness materials into Somali, distributed messages to radio programs, and published on billboards. In March, 25 trainings were conducted, preparing more than 800 health care workers in screening, infection prevention and control, and surveillance.

“Every week, we are challenging ourselves,” said Malik, WHO’s country representative.

“If we want to be sure that this outbreak is contained, there is no alternative than to emphasize containment and mitigation measures.”

Malik describes the operational challenges as severe. Contact tracing, an essential tool in tracking the possible spread of disease, is difficult in remote areas. Health care workers must travel through unforgiving terrain, braving heavy rainfall and the threat of violence. In late May, after a spate of clashes between state security and Al-Shabaab insurgents, seven health workers from a local aid organization were kidnapped and killed in a Somali village.

Some Somalis avoid testing, fearing they’ll be stigmatized by the community. Others do not self-isolate — either because they are living in crowded conditions and are not able to, or they simply do not follow directives — and continue to infect family and community members. Patients often do not go to the hospital until it is too late.

“What we are seeing in Somalia is cases remain undiagnosed, undetected, the self-isolation and quarantine measures are not working as efficiently as we expect them to work,” Malik said.

Older people are suffering the most from community transmission. The country has had 2,779 cases of COVID-19 and 90 deaths, as of June 22, with the majority of deaths falling among people ages 60 to 70. Many of the patients succumbed because of a lack of oxygen in the country’s health facilities. WHO Somalia purchased three oxygen machines to help fill the gap.

INVESTING IN FUTURE RESILIENCE

The country team is working with local and state authorities in Somalia to help them understand the extent and impact of infections. They’re advising on when to ease lockdown restrictions and are sharing modeling techniques and data-driven thinking needed to make informed decisions. This also includes ensuring that other life-saving services such as polio surveillance continue.

“With polio vaccination campaigns temporarily paused, the teams must be able to track any resulting spread of poliovirus and get ready to respond as soon as it is safe to do so,” Malik said

Without this help, Somalia will remain captive to the virus — and that is a risk the international community should not be willing to take.

As UN Secretary-General António Guterres has stressed, an increasingly interconnected world means that “we are only as strong as the weakest health system.”

So far, WHO has helped train more than 4,000 community health care workers in using proper hand-washing techniques and hygiene, identifying suspected cases, and conducting effective contact tracing. Last month alone, community health workers visited more than 300,000 households; more than 6,500 samples were tested in the three laboratories; and more than 10,000 sample collection kits were distributed to federal member states in Somalia.

“We will continue to work as One UN and keep the country safe, showing our solidarity, unity, and partnership with the government,” Malik said.

HOW CAN YOU HELP?

Somalia needs continued support, as heavy rainfall is expected throughout June and locusts continue to threaten crops and food supplies. The World Health Organization not only leads Somalia’s COVID-19 response but also works to prevent cholera, measles, and other infectious diseases. The WHO is indispensable to promoting health in fragile countries around the world.

That’s why we launched the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund. It’s the fastest and most effective way for individuals, companies, and organizations to support the World Health Organization’s work battling the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Read more about WHO’s response to COVID-19 in countries.

TO DONATE

Every donation makes a difference. Support WHO’s life-saving efforts to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by giving to the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund. Donations made via Facebook will be matched up to $10,000,000. Through June 30, 2020, for every $1 you donate here, Google.org will donate $2, up to $5,000,000.

All Photos: WHO Somalia

First Video Credit: FAO

Second Video Credit: UNSOM