Ben Burkett is a fourth-generation farmer in Petal, Mississippi.

His family has been growing food on the same plot of land since 1889, when his great-grandfather received a homestead from the U.S. government just 24 years after the end of the Civil War. It was one of the first African American-owned farms in the state.

Since then, the farm has grown to roughly 320 acres. Depending on the season, his fields grow okra, kale, turnips, rutabaga, watermelon, sweet corn, eggplant, and a wide variety of peppers. He sells his produce to restaurants in New Orleans as well as local grocery stores and farmers markets. Before Hurricane Katrina destroyed his fences, the farm also hosted livestock: Chickens, goats, sheep, cattle, hogs, ducks, and turkeys. In 2014, he won a James Beard Foundation award for his work to support family farming.

From his perspective, there is no question that the climate is changing.

“It’s for real,” he says in his deep Southern drawl. “And we’re gonna have to deal with it.”

The world’s top scientists agree. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a special report detailing how the planet’s land and water resources are being exploited at “unprecedented rates,” threatening the global food supply.

In the past 46 years as a farmer, Ben has watched agriculture change too: Fewer small farmers in his community; fewer young people working in agriculture; huge companies and grocery chains controlling the market; and more farmland being sold for real estate.

“The average person has got to really understand the culture of food,” Ben says. “We take it for granted in this country. We always know it’s gonna be there, but that ain’t a given.”

This is Ben’s story.

My grandfather, Otis Tisdale, always used to tell me: If you take care of this land, it’ll take care of you.

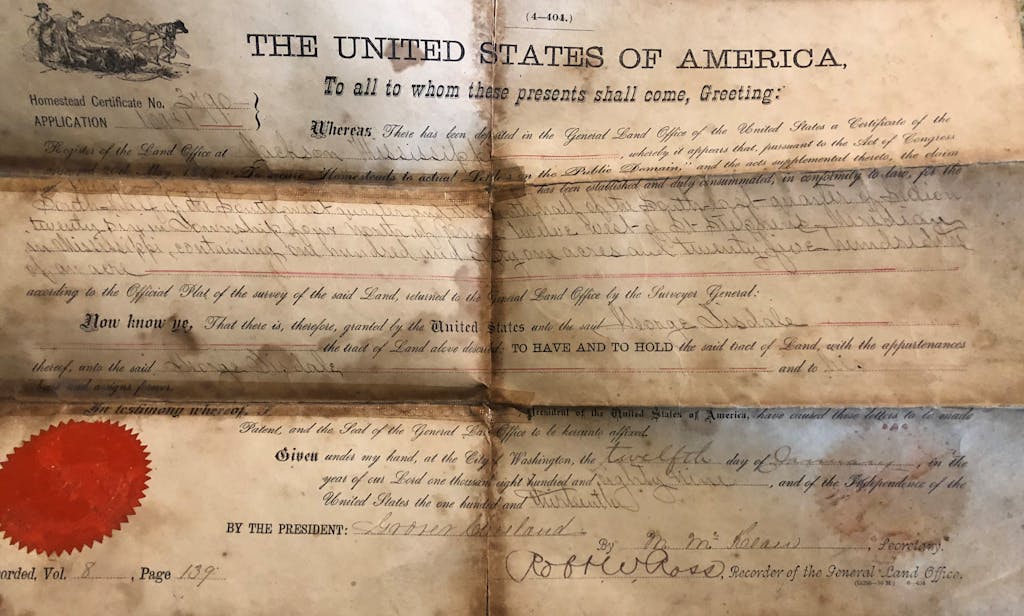

My family’s farm started off in 1889 when he received a homestead from the United States government, signed by President Grover Cleveland. That wasn’t too long after the Civil War. Every generation has added to that homestead to make the farm over 300 acres now. And it’s been a blessing to carry on the tradition of farming in the family.

It’s good soil. All through the winter we can carry turnips, lots of collards, kale, spinach, rutabaga. In the spring, I got bell pepper, hot pepper, sweet corn, and eggplant planted. For summer crops — hot weather crops — we plant okra, watermelon, squash, cucumbers.

I don’t have any livestock on the farm at this time, but over the years we have had chickens, goats, sheep, beef cattle, hogs, ducks, turkeys, all for the market. But because of Hurricane Katrina 14 years ago, it tore up all of my fences. Tore up our church, destroyed whole houses in my community.

The original homestead patent that Ben Burkett's great-grandfather received less than a generation after the end of the Civil War. It's signed by President Grover Cleveland.

After Hurricane Katrina, I was standing in one of my fields and I said to myself, “This field has continued to farm for over 100 years so someone’s been doing some good stewardship of the land.” It’s been a continuous farm all this time.

But you used to be able to plant a crop and know the weather on it. You knew the cycle. Now you can’t time it. Traditionally, the month of May, you’ll get a shower every evening, you could count on it like clockwork. But now that’s done changed.

I attribute that to global warming. I’m not talking theory. Even the cycle of the postseason, even that’s done changed. You used to farm with that cycle. And that cycle is not in place anymore. You can’t count on that rainfall like that.

So you have to irrigate. I have four irrigation wheels on my farm. But it’s nothing like rain water. You can irrigate all you want with groundwater, creek water, service water. Ain’t nothing like a good rain shower on a crop. You would think a state like Mississippi would never run out of water. So that’s putting the pressure on the environment, you know? Using so much water. You have to always keep the soil covered because if you don’t keep it covered, it will erode away or the wind will blow it away. So I use a rotation where every year I plant 10 to 20 acres of organic cover crop like Austrian winter peas or clover.

This past winter, we haven’t had any cold weather. There wasn’t anything at all this winter. We need cold weather. We need ice and snow, now and then. It cuts down on the insect population for the summer. We’re going to have a heavy infestation of aphids and cabbage loopers and all that this year. Those trying to do it organically already know that that’s a battle they’re gonna have to wage.

Ben Burkett credits the rise of farmers markets for promoting locally produced food and creating a sense of connection between farmers and consumers. “The average person has got to really understand the culture of food. We take it for granted in this country."

The community has changed too. It used to be everybody out here was doing some type of farming. Now there’s no more than 10 farmers in my community. I don’t quite understand it. Them that grow up on the farm and out in the country, they don’t wanna be farmers. But the ones who grew up in Detroit and Chicago and downtown Washington, D.C., they wanna be farmers.

There’s the cost for one thing. If you want to stay in the cotton business, cotton could cost a half a million dollars. The combine that thrash corn and wheat cost $300,000 or $400,000. But with technology and equipment, two people growing corn and cotton can farm 5,000 acres. Just two people.

From the Ground Up: Ben Burkett, Mississippi

"It's for real and we're gonna have to deal with it."

Ben Burkett has been farming all his life — and he's got a message about climate change. 👨🏾🌾🌽

Posted by United Nations Foundation on Thursday, August 15, 2019

That’s why we’ve got a farming co-op. That’s the center of our community. We got a packing facility. We can wash crops, grate ‘em, cut ‘em, bag ‘em, anyway you want at that facility. I would say that without that co-op, we probably wouldn’t be in business now, many of us small farmers. And that’s one of the economic hubs in this rural area. It don’t look like much, but a lot money comes through there.

The land’s still there, mostly — lot of farmland just being unfarmed. Lot of it’s been converted to the conservation reserve program. Say I wanna stop farming: I can put my whole farm in the conservation reserve where they’re planting longleaf pine. They done found out that longleaf pine is the best tree to sequester that carbon outta the air. So if I plant these trees, they’ll pay so much for me to plant ’em and give me something every year for the next 20 years to take care of ’em. And the trees is still mine.

Ben stands in his field in Petal, Mississippi. He and his family have farmed the same plot of land since 1889.

Farming is a 24-hour-a-day job. But you feeding people, providing an income for people too. You helping the community.

After the credit crisis of 1989 and 1990, that’s when I got involved in National Family Farm and Rural Coalition and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. I’ve been fortunate to have traveled all over the world because of being a farmer. I’ve met with farmers in Africa, China, the Middle East, South America, Central America. I’ve been everywhere but India. I hope to get there.

All those farmers and family farmers are in the same situation, no matter what country. The same company you see controlling everything here is controlling everything there. You know a lot of times when we go places, they think all the farmers in the United States is rich. I guess they’ve been looking at their television, I reckon. They think all the farmers are big in the United States. But they all are not.

But I learn a lot from traveling around. I came back and put in a raised bed after I went to Cuba. I put in my irrigation in 1988 after studying irrigation at the Volcani Institute in Israel for eight weeks. They helped me design it and I put it in for $3,000. And it’s still working.

130 years after my great-great-grandfather first got this land, we’re still taking care of it, like my grandfather taught me. And so we still got it. We still holding on to it four generations later. With my daughter, it’ll be the fifth. My granddaughter will be the sixth.

The biggest problem they’re gonna have staying in the farming business is subdivisions. It’ll be all the way around it. You know, when a farmer dies and the children don’t want to farm, then a realtor buys it up to build houses on it.

But my great-grandfather would be proud cause the farm is still supporting the family. He would be tickled to death probably. Even my mom, who didn’t want me farming, probably would have been. And many people in the community making money off of it.

Ben poses with his granddaughter, who holds a mini-farm tool and wears a

Ben poses with his granddaughter, who holds a mini-farm tool and wears a

t-shirt that proudly proclaims: “To farm is to touch a life forever.”

We live in a country where we’re used to — I don’t wanna say cheap food — but we’re not used to paying much of our income like the Europeans and other parts of the world. People don’t wanna pay the real cost, you know?

Farmers see these changes happening. Sometimes even professors and universities, they discount us as not knowing but, in reality, we know. It’s for real. And we’re gonna have to deal with it. We’re gonna have to learn how to cut down on carbon emissions. Gotta learn how to use wind power, solar power. We got to better manage water, ’cause we take it for granted in Mississippi but it’s not finite. We might think it is but it ain’t.

We’re gonna have to learn how to do it more sustainable. I think us farmers got it. The average person has got to really understand the culture of food. We take it for granted in this country, you know? We always know it’s gonna be there, but that ain’t a given.

Take Action

Tell your Governor you support bold climate action and stand with the U.S. Climate Alliance.

When the U.S. announced plans to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, it became the first country to join and subsequently intend to pull out of the world’s most ambitious global climate deal, adopted at the United Nations in 2015. As a result, a bipartisan coalition of U.S. Governors came together to send a message: We must do our part to protect the planet.

You can stand with them and step up on climate with our partner organization, UNA-USA, a movement of Americans who support the work of the UN. Send a message urging your Governor to support bold climate action in your state.