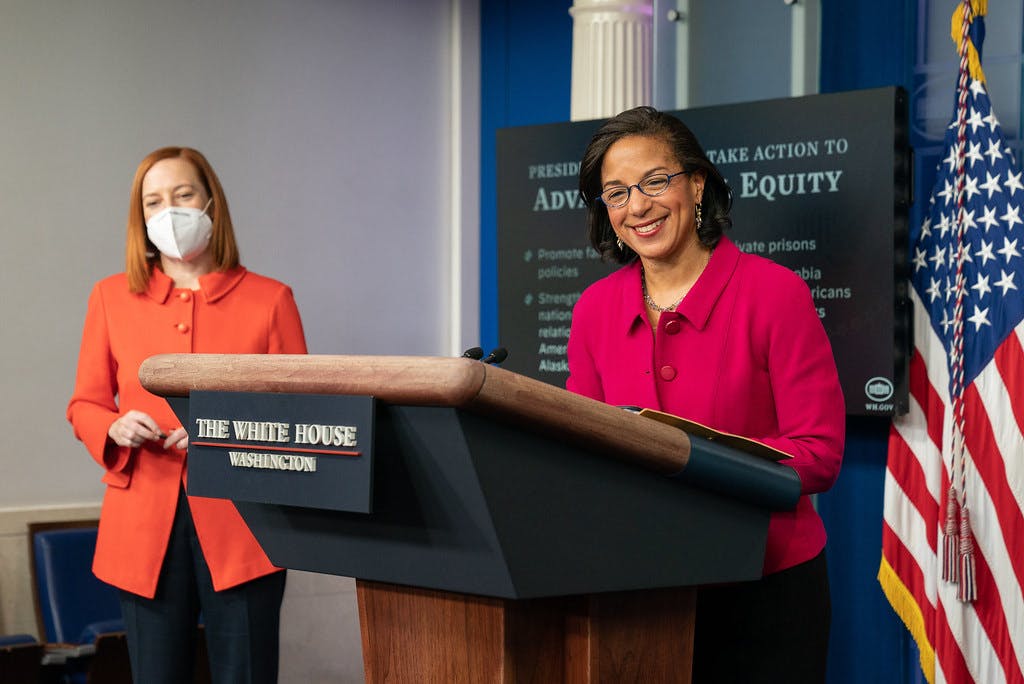

Since the United Nations’ founding in 1945, African Americans have played prominent roles in forging the organization’s mission and work to advance international peace and harmony. Many of them started out as advocates for equality and justice at home, calling the president’s attention to the struggles of Black Americans, or during the civil rights movement. They translated these experiences into deft statesmanship on the UN stage, driving progress on human rights around the world. If confirmed, President Joe Biden’s pick to represent the U.S. at the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, will carry on the tradition of African Americans serving at the highest levels of international diplomacy, helping to foster American engagement and leadership on the global stage.

Here, we profile five of them and some of their many accomplishments:

1. Mary McLeod Bethune

After lobbying her friend, Eleanor Roosevelt — the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt — education champion Mary McLeod Bethune attended the 1945 conference to draft the United Nations charter in San Francisco. According to a collection of her essays and selected documents, “Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World” (Indiana University Press, 1999), Bethune’s role as a consultant allowed her to make recommendations to the American delegation on principles and values to guide the Charter, and to lobby attendees from around the world on the importance of ending colonialism, securing an international bill of rights, and prioritizing education and culture in the UN’s work. She saw similarities between the struggles of Black people in the United States and movements for independence in other countries, especially those in Africa and Asia. Writing about her reactions at the historic gathering, Bethune expressed great pride at seeing groups of African Americans representing political, religious, and fraternal organizations gathered outside the San Francisco meeting, to link their own pursuit of peace and freedom with that of millions around the world. In an open letter about her work, she wrote: “Through this Conference the Negro becomes closely allied with the darker races of the world, but more importantly he becomes integrated into the structure of the peace and freedom of all people everywhere.”

2. Ralph Bunche

Another figure present at the San Francisco conference was Ralph Bunche, a scholar and activist who researched colonialism in Africa and likened it to racial discrimination in the U.S. He played a large role in drafting Chapters XI (on non-self-governing territories) and XII (trusteeship for administering and supervising such territories) and was a key voice for decolonization. Bunche is perhaps best remembered for his work in advancing peace on the Israel-Palestine issue, drafting the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, and organizing the UN’s first peacekeeping mission, the UN Observer Group in Palestine. In recognition of these efforts, he became the first person of color to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. Speaking about his mediator role, Bunche said: “The objective of any who sincerely believe in peace clearly must be to exhaust every honourable recourse in the effort to save the peace.”

3. Carl Rowan

From an impoverished childhood in Tennessee, Carl Rowan would go on to become a nationally syndicated columnist and the first African American to sit in on National Security Council meetings. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy asked him to serve on the U.S. delegation to the United Nations, which according to his memoir, “Breaking Barriers” (HarperPerennial, 1992), he accepted “without much enthusiasm” because he was concerned about being tokenized as the only African American on the team. Despite initial misgivings about the role, Rowan became a key figure during the Cuban missile crisis, shuttling between Washington and New York to communicate the U.S. position. He was also vocal about the inequalities he saw between white and Black American diplomats in the UN delegation, and he brought the discrimination to the president’s attention. Much of Rowan’s writing focused on racial equality in America, and he would often say, “I am a crusader for racial justice, and I will be to the day I die.”

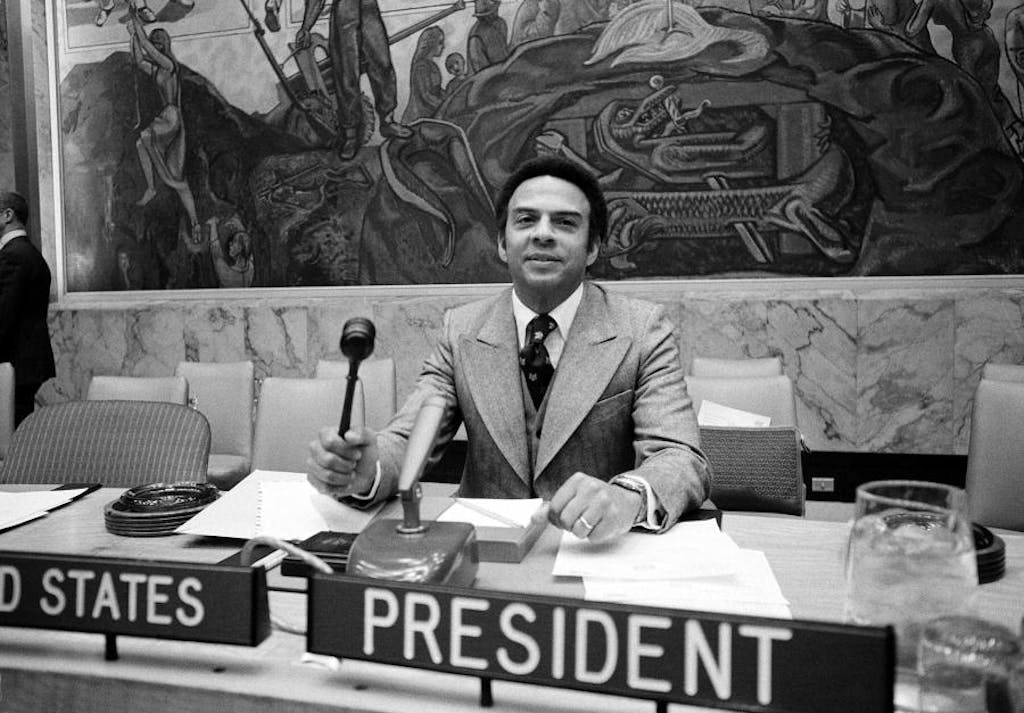

4. Andrew Young

Andrew Young was a key figure in the civil rights movement, working alongside the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. His civil rights work at home inspired him to advocate for similar struggles overseas, and in 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed him to serve as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations — the first African American in the role. As ambassador, Young was not shy to take a stand, speaking out against apartheid and helping his country improve ties with African nations. He advocated for a U.S. engagement approach rooted in human rights as opposed to the dominant Cold War framework. Young is also a former board member of the UN Foundation. Speaking about the importance of the UN, he said, “The UN saves lives . . . we don’t need to try to make everything right by ourselves. If we didn’t have the United Nations, the world would be a far more dangerous place.”

5. Susan Rice

Under President Barack Obama, Susan Rice made history by becoming the first Black woman to represent the U.S. at the UN. During her tenure, she juggled several challenging U.S. priorities including improving governance and addressing the conflict in Libya; tackling the civil war in Syria; and imposing sanctions on Iran and North Korea. Rice is known for her forthright and witty demeanor and approach to diplomacy. In an interview, she explained why the work of the United Nations is more important than ever: “I happen to believe . . . that our security and well-being as Americans are inextricably linked to the security and well-being of people elsewhere. . . . Indifference is costly in moral and humanitarian terms, and it’s costly in security terms.”

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts