As world leaders prepare for the upcoming UN General Assembly (UNGA), the planet is facing simultaneous emergencies that are threatening our collective ability to respond: the ongoing global pandemic, increasingly extreme weather events, and a rise in humanitarian crises with far-reaching impacts for the world’s most vulnerable people, including women, girls, and those who have dedicated their lives in the pursuit of dignity and human rights.

Like last year’s annual convening, this year’s UNGA — which takes place from Tuesday, September 14, until Thursday, September 30 — has been affected by the pandemic with multiple events and convenings taking place online instead of in person.

What can we expect this year? Here are some key issues to watch for.

1. ENSURING VACCINE ACCESS AND AN EQUITABLE COVID-19 RESPONSE, AND PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE

Since March 2020, when COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 4.5 million people have lost their lives to the virus. Countless more have been hospitalized, and more than 200 million global cases have been confirmed — a conservative estimate given limited global testing and spotty data collection. Meanwhile, two-thirds of the planet’s students have been affected by full or partial school closures, and unemployment has risen worldwide, especially among women and young people.

The rapid development of safe and effective vaccines for COVID-19 has been a marvel, helping to stem the mortality tide and allowing us to see the light at the end of an unrelenting health crisis tunnel. However, the path to the other side of the pandemic is far from clear — and far from certain. The spread of the highly infectious delta variant demonstrates the virus’s power and why global solidarity, political leadership, and continued support for science and public health together are our only way out.

The fact of the matter is we can’t defeat COVID-19 until everyone has access to vaccines. We will continue in this cycle of chasing variants unless global leaders make different choices: closing the inequity gap and reversing a widening chasm between wealthy and poorer countries.

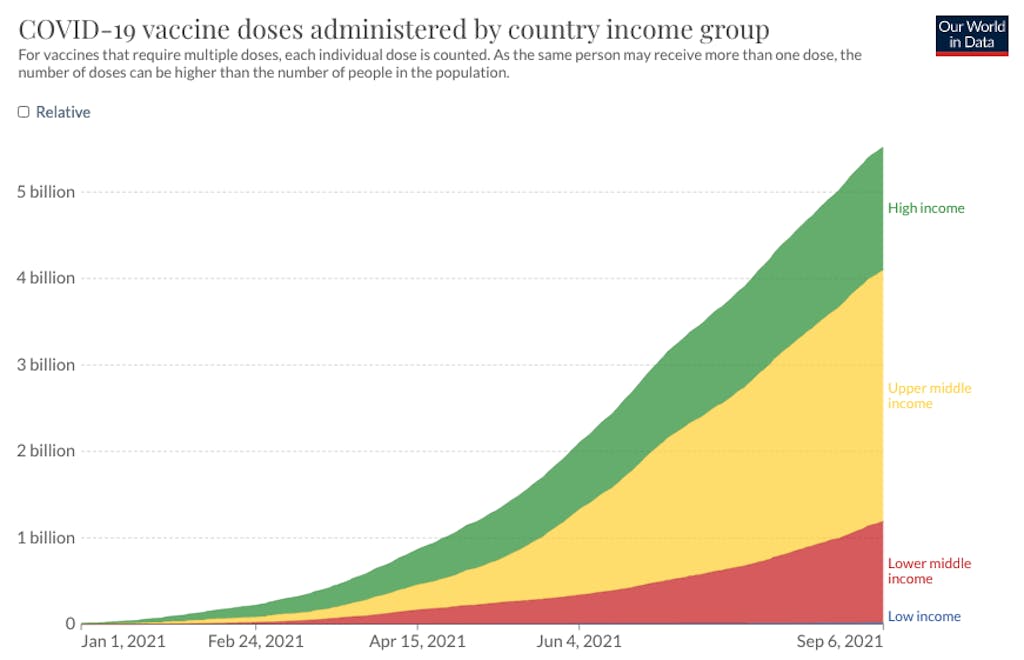

We must correct our course, and quickly. So far, 80% of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines have gone to high-income countries. In low-income countries, meanwhile, only about 2% of the populations have received even a single dose. One of every two people have been vaccinated in wealthier nations compared with just 1 in 47 people in poorer nations.

Such delays mean that low- and middle-income countries are struggling to secure the supplies and resources needed to help them weather the delta variant surge and other challenges related to COVID-19, not to mention building a more sustainable and inclusive recovery out of the crisis.

At this year’s UNGA, ensuring equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments should be at the top of political leaders’ agendas, including at a US-hosted Summit to take place on September 22. It is an opportunity to respond to immediate needs and public calls for greater urgency and action. It follows recent global meetings including the June G7 summit in Cornwall, England, where countries committed to sharing at least 870 million vaccine doses to the vaccine-sharing COVAX initiative, but where progress since then has been slow. The Multilateral Leaders Taskforce on COVID-19, which comprises the heads of the World Bank, WHO, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Trade Organization, recently urged greater sharing of vaccines to address the inequity gap, calling on the G7 leading economies to fulfill their pledges and noting that less than 10% of the pledged doses have been shipped.

At this rate, those in the poorest countries might not have access to a vaccine until 2023 at the earliest. The longer people go without vaccines — especially in places that lack adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing — the greater the risk for overwhelming health systems and accelerating the virus’s spread worldwide.

And then there is the matter of better preparing for the next threat. We know it will be a matter of “when,” not “if.” Long-term solutions are needed to repair and improve health care infrastructure and access. There are also clear gaps and vulnerabilities in pandemic preparedness and response capacities. The world was not prepared for this pandemic. And it is definitely not prepared for the inevitable next one.

Across the diplomatic, global health, and security communities, proposals are being developed to rethink and reform the very regimes responsible for pandemic preparedness and response, from new financing mechanisms to strengthening coordinated global capacities to monitor and assess pandemic risks as well as new or improved governance functions.

UNGA is an opportunity to advance these discussions while demonstrating political leadership and urgent action, especially ahead of the G20 summit planned for October in Rome and the special session of the World Health Assembly in late November in Geneva, Switzerland.

2. ADDRESSING DETERIORATING HUMANITARIAN AND SECURITY CRISES

In addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is facing unprecedented humanitarian needs. Even before the recent earthquake in Haiti and the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, a record 235 million people — 1 in 33 worldwide — were expected to need humanitarian assistance this year. Protracted conflicts and violence, climate-related disasters, and political and economic crises have increased the total number of displaced individuals to 82.4 million over the past year, the highest in recorded history.

The rapid Taliban takeover in Afghanistan revealed drastic threats to human rights and security in the region, particularly for women and children. Close to 570,000 people have been displaced in the country. The UN estimates that nearly half the country’s population — 18.5 million people — will require humanitarian support this year. The UN’s recent high-level ministerial meeting included a flash appeal to ensure that the critical needs of the people of Afghanistan—including women and girls—continue to be met in the weeks ahead.

At the same time and on the other side of the world, a double catastrophe hit Haiti. A 7.2 magnitude earthquake followed by Tropical Depression Grace left nearly 2,000 people dead. The twin catastrophes affected more than 1 million people and left half a million children with disrupted or no access to safe shelter, water, or nutrition.

Unfortunately, Afghanistan and Haiti are only the latest — and not the last — examples of the humanitarian crises and risks to global peace and stability that rack our world. Conflicts in Yemen, Ethiopia’s Tigray region, Syria, and Central America have forced millions to flee their homes and continue to strain financial resources for humanitarian aid.

At UNGA, leaders will take these challenges forward, including on matters related to safeguarding human rights and protecting women and children in Afghanistan. Coordination with the UN Security Council, chaired by Ireland in September, will be necessary to address security concerns and multilateral response needs.

More broadly, discussions will take a holistic look at how conflicts drive and shape other issues, including food insecurity — which hit a five-year high in 2020 — girls’ and women’s rights, and education. And the Security Council is expected to hold an open debate on climate security as a way to elevate the role that climate increasingly plays as a contributing factor in many of the conflicts facing us today.

3. MOBILIZING AMBITIOUS CLIMATE ACTION BEFORE IT’S TOO LATE

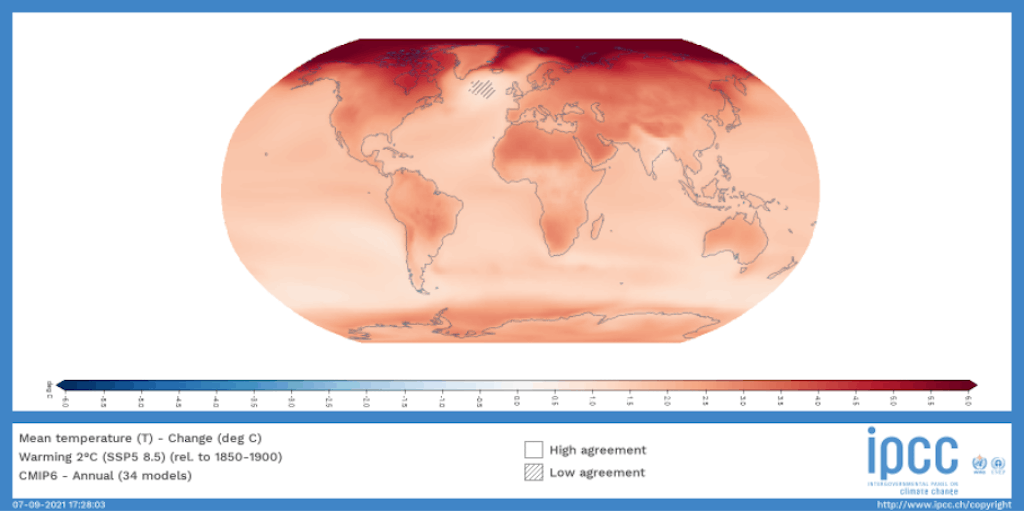

In what UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called a “code red for humanity,” the newly released report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows that climate change is widespread, rapid, and intensifying. Even with most of the world on lockdown last year and emissions temporarily dipping, the planet continues to warm. Over the past few months, emissions have not only recovered from their COVID-19 lull, but are surging to new heights. This July was the hottest month ever recorded. Deadly floods swept Europe, the United States, Nigeria, and China. Wildfires ravaged Greece, and the western U.S. Greenland’s ice summit witnessed rain for the first time in history.

The more our planet warms, the more dire environmental, economic, and social consequences will be. Recognizing this, many voices — including youth leaders and civil society — continue to sound the alarm. Greta Thunberg, on the third anniversary of her starting the now global movement of protests to bring attention to the climate crisis, decried the unfairness that is young people who “will have to clean up the mess you adults made.”

This year’s UNGA offers a critical moment for countries to demonstrate resolve and ambition on climate action, especially as world leaders head into the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November in Glasgow, Scotland, when national governments must submit enhanced action plans and targets as part of the Paris climate agreement.

Climate finance for developing countries will likely be a key focus as wealthier nations face mounting pressure to deliver on their commitment to provide $100 billion per year to support poorer countries that are disproportionately facing the consequences of climate change despite being among the lowest carbon emitters.

Another will be on how to transform hard-to-abate sectors such as cement and aviation, as well as how to continue to put pressure on governments and multilateral institutions to ensure that COVID-19 recovery plans are greener, fairer, and more sustainable.

The Secretary-General will convene a closed door climate session on Monday, September 20. Meanwhile, Climate Week NYC — a coalition of civil society, government, and private sector leaders — will host virtual events to discuss next steps in the net-zero movement to offset new greenhouse gas emissions by removing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

And Secretary-General Guterres will convene the first-ever UN Food Systems Summit in September to examine how food systems can advance progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The global food system is one of the largest contributors to climate change, responsible for one-third of all planet-warming emissions. At the same time, the sector is especially vulnerable to climate change shocks. Secretary-General Guterres will also host a High-level Dialogue on Energy in September to promote energy-related targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This will be the first UN conference dedicated to this topic under the auspices of the UN General Assembly in over 40 years. Member States, companies, regional and local governments, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) will have the opportunity to register commitments toward SDG7 (Access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all) through “Energy Compacts.”

4. ACHIEVING THE SDGs AND LEAVING NO ONE BEHIND

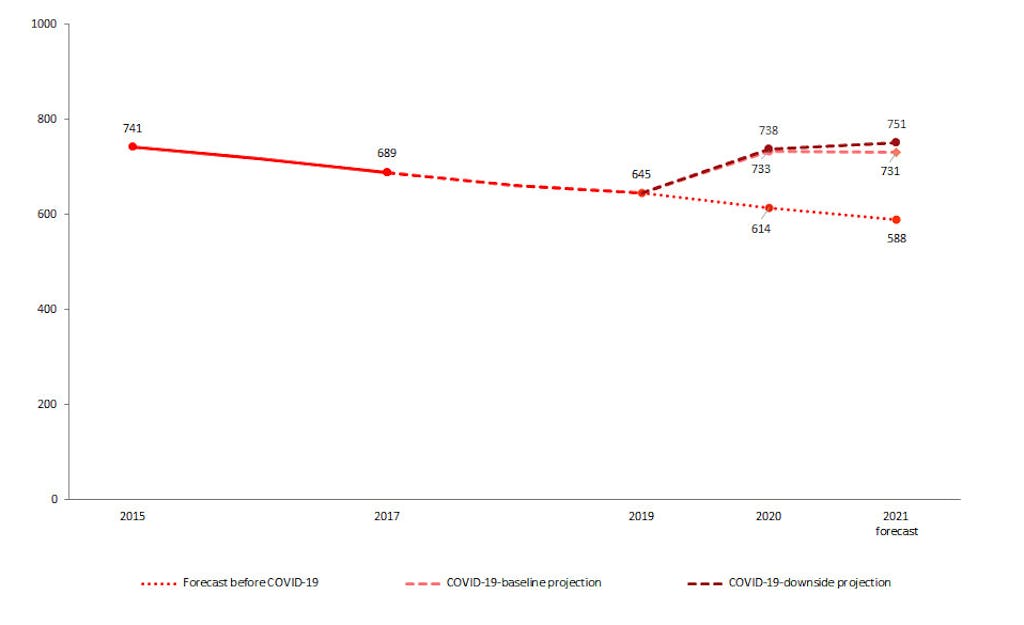

The world is at a critical point in our commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals. They set out an ambitious agenda to address the world’s most pressing issues — climate change, inequality, and poverty — and build a sustainable, resilient future that promises to leave no one behind. The ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have slowed and reversed progress on a number of social and economic issues.

Extreme poverty is on the rise for the first time in a generation, with 119 million to 124 million more people pushed into extreme poverty in 2020 alone. According to the UN World Food Programme’s global hunger map, more than 900 million people do not have enough to eat. More than 100 million children now have reading proficiency levels that are below the minimum.

Our commitment to the SDGs offers a path to shape the world moving forward with an innovative, inclusive recovery.

At UNGA, leaders are expected to emphasize the SDGs as a practical set of solutions for tackling our interconnected, present-day problems.

It should also acknowledge and respond to the pandemic’s secondary impacts, particularly on those who are bearing the greatest burden: women, children, impoverished households, and marginalized populations. An estimated 47 million more women have been pushed into poverty as a result of the global shutdown, 10 million more girls are at risk of child marriage over the next decade, and women suffered the highest rates of domestic violence over the last 12 months than ever recorded.

The pandemic has also highlighted and exacerbated inequalities within and between countries. As the Secretary-General continues to stress, wealthier countries have created robust recovery plans while the poorest countries are limited by resources to both respond to their immediate needs and recover more sustainably. The inequity risks creating a deep recovery gap that could take decades to correct, delaying and complicating efforts to address extreme poverty and leave no one behind.

This concerning trend points to the need for serious and stepped-up efforts around financing to support lower-income countries. The IMF recently announced it would allocate Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) equivalent to $650 billion to increase global liquidity and support the most vulnerable during recovery. While this is a positive step forward, it is not nearly enough. The IMF is developing pathways for richer states to transfer SDRs to lower-income countries in need. While the UN Secretary-General has provided leadership in launching new, multilateral policy approaches to financing development in the short and medium term, a comprehensive, long-term approach to the financing challenge is needed.

Additionally, there is likely to be an increased focus on local action on the SDGs, which featured prominently in the July High-level Political Forum. We will continue to see strong and innovative leadership from local and subnational leaders across sectors who embrace the SDGs as a path forward.

5. FORGING A COMMON AGENDA AND THE FUTURE OF COOPERATION

As part of UNGA 76, the UN Secretary-General will release Our Common Agenda, his vision for updating a multilateral system that was created in the aftermath of World War II. This includes building trust in a fractured world, tackling the digital divide, and ensuring that future generations will have a habitable planet to call home. It also means mobilizing commitments, creativity, and political will from different demographics — including young people and civil society — to help give shape to the UN’s commitment toward a more inclusive and networked multilateral system.

A more effective multilateral system will have to manage an increasingly geopolitically fraught environment, where differing worldviews vie for control over norms, values, and the principles that govern and orient our collective challenges. It must also navigate against the backdrop of national governments increasingly contending with domestic challenges and fissures that demand significant resources and attention.

But the challenges our world faces are ones we increasingly share, which means that our response must also be collaborative.

This year’s UNGA is an opportunity to build stronger, more sustainable, and more creative channels of global cooperation.