Editor’s Note: This post is the third in a series of blog posts on the founding of the United Nations 70 years ago. You can read the first post here and the second post here.

Eight female delegates attended the San Francisco conference to create the United Nations Charter. Only one country sent two female delegates – Great Britain.

Ellen Wilkinson and Florence Gertrude Horsbrugh were an integral part of Britain’s team at the conference, and they were skilled politicians at home.

As a young woman, Ellen Wilkinson became involved in the suffragette movement and worked as a trade union organizer. Although she was a founding member of the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1920, Wilkinson left to join the Labour Party a few years later. In 1924, she stood as a Labour Party parliamentary candidate. Wilkinson was the only woman elected for the Labour Party that year. During World War II, she worked at the Ministry of Home Security as a Parliamentary Secretary. Wilkinson became known as the “shelter queen” for her work in providing adequate shelters to families affected by aerial bombardment.

Just a few months after returning from San Francisco, Wilkinson became the second-ever woman to earn a place in the British cabinet. She became Minister of Education in August 1945. Wilkinson dived into implementing the 1944 Education Act. She later introduced free school milk and raised the school leaving age from 14 to 15.

But Wilkinson did not stop her involvement with the UN. In October 1945, she traveled to Germany to investigate the rebuilding of the decimated German school system. One month later, in November 1945, she chaired the international conference in London that spearheaded the creation of UNESCO. Sadly, Wilkinson died shortly afterwards in 1947.

The other British woman to travel to San Francisco was Florence Horsbrugh. She would follow in Wilkinson’s footsteps and become the third-ever woman to hold a cabinet position.

Horsbrugh (later Baroness Horsbrugh) and Wilkinson were very different characters. Wilkinson was a socialist and Labour Party MP. Horsbrugh was educated at private schools and became a Conservative MP in 1931. Wilkinson came from a working-class family in Manchester. Horsbrugh came from north of the border and was the MP for Dundee. But she was just as devoted as Wilkinson to international cooperation and to issues surrounding women and children.

Like Wilkinson, Horsbrugh became a Parliamentary Secretary during World War II. While Wilkinson became the “shelter queen,” Horsbrugh was the evacuation empress. She worked as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health and organized the evacuation of 1.2 million mothers and children from major cities to the countryside. Horsbrugh also worked extensively on laying the groundwork for what would become the National Health Service.

Horsbrugh had long been involved in international organizations. She served as a British delegate to League of Nations assemblies three times in the early 1930s. And she traveled with the British parliamentary delegation to San Francisco to work on the UN Charter.

Shortly after her return to Britain, Horsbrugh was voted out of office in the July 1945 election that also saw Winston Churchill lose power and shocked conservatives. Clement Attlee’s Labour Party won a majority of 145 seats, and Ellen Wilkinson entered the cabinet.

But Horsbrugh’s parliamentary career did not end there. She was elected as an MP for Manchester Moss Side in 1950. She became the first woman to enter the cabinet of a Conservative government and served as the Minister for Education from 1951 to 1954. From 1955 to 1960, Horsbrugh acted as a delegate to the Council of Europe and the defensive alliance of the Western European Union.

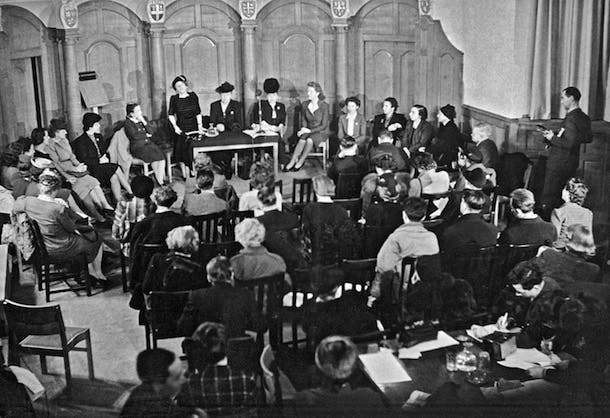

Wilkinson and Horsbrugh were full participants in the San Francisco conference. Like other delegates, they sat on multiple committees. But their role is often underappreciated. One historian has called Horsbrugh “the Conservative Party’s forgotten first lady.”

After the U.S., France, the USSR, and New Zealand had ratified the UN Charter, Great Britain took on the task. Starting on August 15, King George VI gave a speech pushing for the Charter’s ratification. Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin and Prime Minister Clement Attlee followed up with impassioned speeches. Attlee declared that the UN Charter was “an endeavor to put into practical form the deep feelings of all the peoples, including the fighting men who have made it possible to have a Charter at all.”

But it was not just men who made the UN Charter, as Attlee himself acknowledged by thanking the British delegates at San Francisco. Out of the UK delegates who travelled across the Atlantic to create the UN Charter, two were women.

Heidi Tworek is an Assistant Professor of International History at the University of British Columbia.

UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts