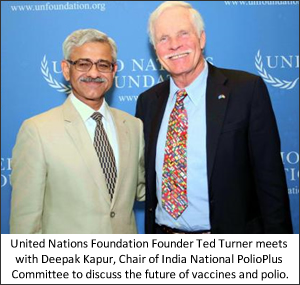

I’m in India this week with the United Nations Foundation’s Board of Directors – some of the smartest minds I’ve ever had the pleasure to work with – to discuss how we can help the UN solve some of the world’s biggest challenges. As we are in India, polio eradication is an issue that figures prominently in our discussions.

India went from having half of the world’s polio cases in 2009 to becoming free of the disease in January 2012. This is a major milestone that should be celebrated. The Government and people of India, committed NGO partners collaborating with the Polio Eradication Initiative, and the tremendous work of Rotary International, the United Nations, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation all were part of this effort. But we must stay focused on the goal of eradicating polio from the planet. After all, a 99 percent reduction is not 100 percent eradication.

India went from having half of the world’s polio cases in 2009 to becoming free of the disease in January 2012. This is a major milestone that should be celebrated. The Government and people of India, committed NGO partners collaborating with the Polio Eradication Initiative, and the tremendous work of Rotary International, the United Nations, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation all were part of this effort. But we must stay focused on the goal of eradicating polio from the planet. After all, a 99 percent reduction is not 100 percent eradication.

Unless polio is eradicated rapidly from the remaining endemic countries – Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan – it will continue to re-infect polio-free countries. Over the past three years, approximately half of all global polio cases occurred in polio-free countries, because of importation from endemic areas.

Failure to eradicate polio now could result in as many as 200,000 new cases every year, within ten years. Success on the other hand will mean that no child will ever again know the pain of being paralyzed for life, and the world will reap financial savings of more than $50 billion through 2035.

How did India accomplish this significant milestone in the fight against polio? Examining India’s accomplishments can help provide key lessons for the other countries trying to do the same. I see these points as being key to India’s achievement:

- Strong leadership and political will at every level of government

The government set up an India Expert Advisory Group to help overcome huge hurdles, such as its high birth rate, large population, hard-to-reach migrant communities and resistance to the vaccine in high-risk populations, to stop polio. - Financial resources and commitments from the government and public/private organizations

India is projected to have spent close to $1.5 billion of its own funding to tackle polio by the end of next year, matched by approximately $9 billion in commitments to the global eradication effort by key donors like the U.S. Government, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Rotary International. In this economic climate, dollars are tight, these remarkable investments have demonstrated what a priority this issue really is. - Many dedicated, trained health workers and volunteers

India had 2.3 million volunteers across the country immunizing children from urban centers to rural areas. Vaccinators went to train and bus stations and festivals to reach migrant and highly mobile groups. This army of supporters administered over 900 million doses of oral polio vaccine, reaching an unprecedented 99 percent coverage rate in the two states where polio remained endemic, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, a feat that had not been accomplished anywhere else at this scale. Even India’s famous Bollywood got involved, with key leaders like Amitabh Bachchan motivating the nation to meet its goals. - Public-private collaboration

No one organization can know and do everything. India relied on support from a number of partners including the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for technical and planning assistance, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for critical funding and social mobilization support, local community-based organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and many others. Impressively, nearly 119,000 Rotarians in India chipped in to raise awareness, organize vaccination campaigns, and deliver vaccines as part of Rotary International’s steadfast commitment to ending polio worldwide.

- Embracing innovation and technology to respond more quickly to outbreaks.

Laboratory improvements cut the time to diagnose polio in half, and the introduction of genetic sequencing helped pinpoint the origin of the virus. The introduction of a new bivalent vaccine, starting with trials in India in 2008 and 2009, provided for a higher degree of protection while saving costs.

These are critically important lessons that can resonate for virtually any global public health challenge, from measles elimination to malaria prevention. Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan have never stopped polio transmission, and we owe it to those three countries – and to India – to remain committed, supportive, and engaged in helping them rise up to meet the opportunity of eradication head on.

The partnership that brought together the Government and the people of India, its partners and friends to tackle this disease is a story of tenacity and steadfastness. We should learn from this example and re-commit ourselves to building awareness and advocating about the value of vaccines around the world, through programs like the UN Foundation’s Shot@Life campaign. It is a way each of us can ensure that more countries can join the list of places free from preventable diseases. It is a way each of us can help build a better world.

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts