Dr. Peter Hotez can’t sleep.

As one of America’s leading vaccine scientists, he oversees a team of researchers that’s working on not one, but two COVID-19 vaccines that he’s hoping will begin clinical trials soon.

“I’m getting up at 4 a.m.,” he told me from his home in Houston, Texas, where he serves as director at the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital.

“It’s a combination of being terrified of what’s going on and also energized.”

Dr. Hotez happens to be an expert in coronavirus vaccines in particular. In March, he testified before Congress about developing a vaccine during the SARS epidemic in 2003 that sat untouched in a lab freezer; his team couldn’t secure enough funding to begin clinical trials.

I recently spoke with him about the global quest for a COVID-19 “cure,” what he thinks the average person should know about the World Health Organization (WHO), and why everyday working scientists like him can no longer remain invisible.

MJ: I want to start by going into your experience with coronavirus vaccines — and what makes COVID-19 so different from previous outbreaks.

Dr. Hotez: This current COVID-19 outbreak is actually in some ways our third major coronavirus pandemic.

We had Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome — SARS — in 2003, which originated in southern China, spread into Toronto and elsewhere. Then we had the Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome — MERS coronavirus — in 2012 from the Arabian Peninsula.

And now we have COVID-19. We know this virus replicates in the upper airways more than the other coronaviruses do — like SARS or MERS — and is, therefore, more transmissible. So you have this virus being transmitted when people cough, or sneeze, or even speak, as the virus can be aerosolized this way. Also, there are the asymptomatic infections — people with no symptoms.

Then there are those who get very ill, winding up in the Intensive Care Unit or experiencing sudden death because this virus is attaching to a unique receptor called the ACE2 receptor that’s found in the heart and the endothelial cells lining the vasculature and in the lung tissue and even the nervous system.

So we’re seeing this unique constellation of symptoms and syndromes, including severe pneumonia, inflammatory responses to severe heart disease, to clotting disorders, and even neurologic dysfunction.

We’re still learning a lot about this virus. It’s only been around for months, but the scientific community is applying technology to combat this virus in ways we’ve never seen before. And we’re going to need a vaccine because this virus is so highly transmissible. And when you have so many people without symptoms, how else do you trace the contact?

So this really means a vaccine is the number one global priority right now.

“Corona” is the Latin word for “crown.” (Alissa Eckert, Dan Higgins/CDC)

Can you talk a little bit more about what this vaccine research looks like and why global cooperation among the scientific community has been so important?

Well, it turns out the technological achievement to develop a COVID-19 vaccine is actually not very complicated.

If you look at a cartoon of the virus, it looks like a ball or a donut with some nucleic acid in the middle and spikes sticking out, and these spikes have little rounded ends. And indeed that protein is called the “spike protein.” At the end of it is a piece called the receptor-binding domain. That’s the part that docks with the receptor in human tissue called the ACE2 receptor, which allows the virus to gain entry into the heart, and the lungs, and the vasculature, and other tissues.

So by making an immune response against the spike protein in some capacity, you have a very good vaccine strategy.

That’s the easy part.

The hard part is how do you do that in a way that’s both efficient and safe?

The problem is this: We’ve spent a lot of time in laboratory animal studies showing that our vaccines are safe, but you still have to show that it works in people — and accelerating those studies in humans is hard.

Historically, it’s taken years to show that vaccines are both safe and effective. In fact, there’s a recent paper in Nature saying 90% of all vaccines that start clinical trials never make it to the end, either because they’re not eliciting an effective immune response or there’s some safety concern and they drop out.

Now here’s the challenge. We’ve been told by Dr. Anthony Fauci, who heads the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, to have a vaccine ready in a year to 18 months. How do you do that? I’ve devoted my life to developing vaccines and it can sometimes take a decade or even two decades to get a vaccine all the way through from discovery through clinical development.

How do you compress that timeline? One way is to get dozens of different vaccines into the pipeline with the hope that maybe only two or three of them will emerge at the end of it. So you need to explore these different vaccines because you’re trying to stack the deck in your favor of getting two or three that seem to be effective. That’s the strategy.

So you’re hearing in the lay press that there’s a race for a vaccine. And I would imagine it sort of looks like a horse race with all of these vaccines underway at the same time, but I personally don’t consider it a race. If our vaccine doesn’t make it to the finish line and another one does, it still helps humanity. Each of those dozens of vaccines has different strengths, each of those dozen vaccines has different weaknesses, and there’s really no way to predict which one or which several are going to emerge as successful.

What are some other misconceptions you’re hearing about COVID-19 vaccine research that you think should be dispelled?

We have to get away from this notion that there’s just going to be one vaccine. It’s not going to be like the Jonas Salk polio vaccine was in the 1950s where everybody lines up to enter the auditorium of the University of Michigan and out steps somebody like the Wizard of Oz behind the curtain to say, Here it is.

That’s not going to happen. You’re going to see several vaccines with different uses. So for instance, some vaccines will be effective mostly targeting the people at highest risk of getting severely ill or dying. There may be a vaccine that’s uniquely tailored to people with underlying chronic morbidities such as diabetes or heart disease. There may be a vaccine that can elicit a rapid immune response for healthcare workers since we’re seeing so many healthcare workers get sick. There may be one for first-line responders. Or one for pediatric use to start immunizing kids when they’re adolescents, like the HPV vaccine.

I want to go back to the race metaphor. I read a New York Times article recently that warned about how this “race” for effective COVID-19 treatments and vaccines is becoming the “new nationalism” as world leaders jostle each other for access and control.

Can you talk about the risks this zero-sum mindset poses — particularly a trade war between China and the U.S.?

This was something I was hoping would not happen, but I do think it’s a potential risk, especially for some of the vaccines that use newer technologies like some of the MRNA vaccines that have a unique type of packaging.

That’s why I think we’re going to need multiple different types of vaccines. Our team has been making vaccines for poverty-related diseases for decades. Most of those use technologies that could be relatively easily scaled and even manufactured in disease-endemic countries.

So for instance, our COVID-19 vaccines — we have two in development — use a recombinant protein technology made in yeast. And you might ask, well, what’s the advantage of that? The advantage of that is it’s the same technology used to make the recombinant protein Hepatitis B vaccine that’s already scaled up and made in places like India and Brazil. So we think these have the potential to be easily deployed and manufactured locally. That’s number one.

Number two, our vaccines are done in a high-producing yeast strain, so it’s cheap. One of the things the Gates Foundation taught us is that you have to have an access plan for low-income communities. For us, there’s no point in making a $500 vaccine if it can’t be used in the slums of Mumbai or São Paulo. Through our previous partnership with the Gates Foundation, we learned how to make things in an inexpensive way.

That’s again why this isn’t a global race. If it turns out in the U.S. that the optimal vaccine is a very expensive piece of RNA embedded in all sorts of elaborate infrastructure, that’s fine. And maybe over time a vaccine like that could come down in price and be accessible for the world. But in the meantime, we’ll roll ours out and be able to start vaccinating across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. So that might be one way all of this plays out.

But you know, we’re still at a very early stage. Vaccines are just now entering clinical trials and we’ve never done this before, if you look at how quickly this vaccine research has been accelerated. For a while I was saying in interviews that the record for fastest vaccine was the Ebola vaccine, which began clinical testing in West Africa in 2014 and wound up vaccinating 200,000 people through the great work of all the UN agencies, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, MSF, Wellcome Trust, Gates Foundation, and [Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority] BARDA … The list goes on. And that work was done over a period of five or six years.

But then I was talking to my friend and colleague Paul Offit, who wrote a great biography of Maurice Hilleman — the scientist who’s probably made more vaccines than anyone — and it turns out the fastest vaccine ever developed in history was the mumps vaccine — and that took four years.

But that’s the bar we’ve set — from a record vaccine timeline of four years to now hoping we can do this in a year or 18 months. I don’t know if we can do it, but I’m getting up at 4 a.m. and can’t sleep. It’s a combination of being terrified of what’s going on and also energized. I’ll text my science partner of 20 years, Dr. Mary Elena Bottazi, who co-directs the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development, and I’ll see that she’s already been up for 45 minutes and sent me a text at 3:15 a.m. That’s what our life is like.

Last year you spoke at the UN Foundation’s Shot@Life Summit, a grassroots campaign that supports global immunization efforts through UNICEF and partners like Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance.

Why do you think championing these organizations is so important — particularly to different demographics and media outlets?

There’s a few considerations. One, right now we’re in the middle of an era when we’re seeing the rise of populist regimes and extreme nationalism. We’re seeing this in the United States with the Trump Administration, we’re seeing it in Brazil with the Bolsonaro regime, in Italy, and multiple other places. And I think it’s more important than ever to speak to a diverse array of people with different political ideologies.

The other thing I try to do as a scientist is to remain humble about what we know — and what we don’t know. This is a brand-new virus pathogen, so to say anything in a definitive or dogmatic way — without acknowledging that we’re still on a steep learning curve — is also a form of misinformation. I’m the first to get up and say, “Look, we’re still learning a lot.”

Even the things I’m telling you today may look very different a couple of weeks from now because it’s not just everything we’re learning about this virus, but also the pace at which we’re learning it. I’ll look back on things I’ve said about this virus in January and think, Oh my God, what an idiot I am. And that’s what new virus pathogens do. They set us up to make us look stupid.

At the same time, we need to take the time to explain complicated scientific concepts without using a lot of jargon. I think that’s important because some of the public briefings about COVID-19 and an earnest attempt to try to explain things means information is often dumbed down to the point where it’s barely even true. And then people pick up on that and start to question what they’re hearing.

We’ve never really figured out how to combat anti-science. I have a paper that came out in Plos Biology that basically says part of the problem is the fact that scientists have largely been invisible. We’re not recognizable to the public and we can’t assign a person or a face to science, so that’s created a gap in understanding and trust. That’s another reason why I’m out there doing interviews.

I think maybe one of the silver linings to this whole tragedy of the COVID-19 pandemic is that people are finally hearing from scientists and they are seeing us in our labs or, in some cases, in our living rooms.

I want to go back to your point about how so much of this scientific work — and the men and women behind it — are invisible, particularly the work of WHO. I think a lot of people have a basic sense of what UNICEF does, whereas with WHO, most people don’t know that it’s an agency of more than 7,000 people in 150 countries — doctors, nurses, scientists, researchers, health care workers, logistics experts, you name it.

I can’t stress enough how important WHO is — especially when you talk about this virus moving into places like Ecuador. Look what’s happening in Guayaquil, the bodies are literally piling up on the streets.

Who’s going to take that on? Who’s going to help Tanzania when this virus moves into Dar es Salaam? If this virus moves into the crowded slums of Lagos or Dhaka, who’s going to help? We need WHO more than ever.

One of the things I’ve been explaining is how modest the budget of WHO is. It’s only about one-fourth of the budget for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. So for a quarter of the budget that the CDC uses to help public health in America, WHO has a mandate for the whole world. Consider how much work they do for so little amounts of funding. And that’s actually true of all the UN agencies [and partners]. UNICEF operates on a shoestring. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance never has enough money.

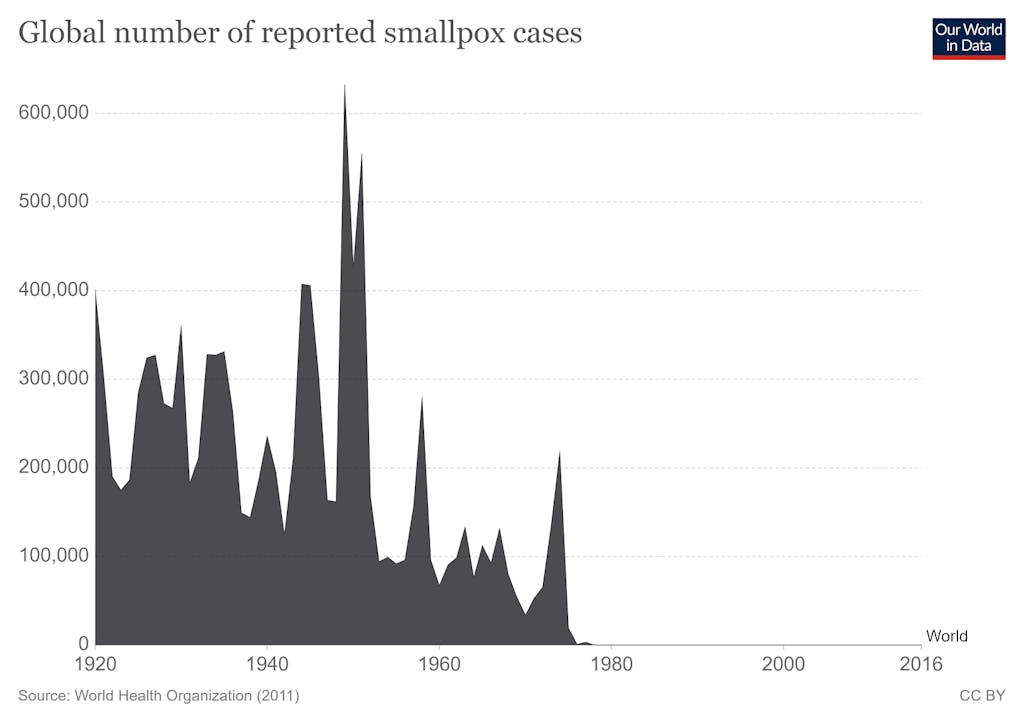

These are lifesaving institutions with proven track records. How do you think smallpox got eradicated? Why do you think we’re near the elimination of polio? That happened because of these agencies.

The problem is there’s limits to how much they can advocate for themselves. That’s why I try to spend so much of my effort advocating for WHO, UNICEF and GAVI — and why the UN Foundation and the Shot@Life campaign are so absolutely critical.

I’m really glad you brought up the proven track record of these UN agencies — not just in eradicating smallpox, but in vaccinating almost half of the world’s children.

WHO just warned that an estimated 117 million children might miss the measles vaccine this year because of the ongoing pandemic. Can you touch on why we can’t lose sight of other potential disease outbreaks while we’re dealing with COVID-19?

One of the most dangerous collateral effects of COVID-19 is how it overwhelms health systems and disrupts efforts to deliver other medicines and vaccines.

We’ve made great gains against diseases like measles and polio, but there are lots of things now working against us that could cause this progress to unravel: We’re seeing political unrest in Congo, what’s going on in the Middle East with the wars in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Climate change is now a risk factor. Aggressive urbanization outstripping infrastructure.

All of this was pre-COVID and now you throw COVID-19 on top of that? I’m very worried and I’m worried on multiple levels. I’m worried about interrupting the good work of the UN agencies committed to health, but I’m also worried about how this pandemic could help foment political unrest, which we’re seeing already. I’m worried about the summer in the United States as the tensions arise between the need for social distancing versus personal liberties. This is a powder keg, especially coming in the fall of what’s going to be a very contentious election in the U.S.

This is going to be a very tense time for the world. All I can say is now we need our UN agencies more than ever.

GET INVOLVED

You can support WHO and UNICEF’s work to stop the spread by giving to the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund. Donations made via Facebook will be matched up to $10 million. Through June 30, 2020, for every $1 you donate here, Google.org will donate $2, up to $5 million.

With more than 350,000 supporters like Dr. Hotez in all 50 states, Shot@Life is a grassroots advocacy campaign of the United Nations Foundation that champions global childhood immunization by supporting the work of UNICEF, WHO, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

To learn how you can join the Shot@Life movement, visit ShotAtLife.org.

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts