By ElsaMarie D’Silva, Founder & CEO of Safecity

Last week I spoke at the Women of the Future Summit in London and asked a room of over 350 women delegates from around the world to raise their hands if they have never been sexually harassed in their life. Not a single hand went up. It came as a shock to me as I was honestly expecting a few hands to be raised.

But I should not have been surprised given the recent outpouring on social media regarding the #MeToo campaign.

Sexual violence is a global pandemic affecting on an average one in three women according to UN Women. In countries like mine in India, it is close to 100%, and yet most of us do not report it for fear of bringing shame to ourselves and our families, fear of dealing with the police and their insensitivity, and fear of the lengthy judicial process for justice.

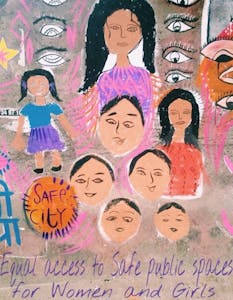

I started Safecity, a crowd map for sexual violence in public spaces, in response to a horrific gang rape of Ms. Jyoti Singh on a bus in Delhi in December 2012. Through our platform we encourage people to share their stories anonymously if they wish to and these are then collated as location based trends, visualized on a map as hotspots. The aim is to make this information available in the public domain, so that neighborhoods can be made safer through individual awareness, collective community engagement, and institutional accountability.

Thus far, we have collated close to 11,000 personal stories from not only India but also other parts of the world like Kenya, Nepal, and Cameroon. We use the online data that women and girls share to identify factors that lead to behavior that causes sexual violence and help us think through strategies to find solutions. We have successfully used the information to engage over 400,000 citizens, police, municipal, and transportation authorities in India and abroad.

We have several examples where our data have led police to change beat patrol timings and increase patrolling. Municipal authorities have fixed street lighting and made safe public toilets available. And together with a partner organization in Nepal, we pressured the transportation authorities to issue “women only” bus licenses.

Data are powerful and can help us identify harassment hotspots as well as the right stakeholders to engage. For example, in Kibera, Nairobi, a hotspot where young men were groping girls on their way to school was near a mosque. My partner organization invited the Imam to a discussion and showed him the data. He went back and incorporated anti-harassment messaging into his sermons. It had a positive impact amongst the young men, and the groping subsided.

In another example, one of the hotspots in an urban slum in Delhi was at a public toilet where there was no proper lighting, doors, or windows. To aggravate the situation, young men sat on a couch immediately outside the toilet and harassed the women and girls using it by commenting, staring, and taking pictures through the broken windows. Imagine if this is your only option for a toilet. It would not only affect your bowel movements, but you would also restrict your intake of food or water to minimize your trips to the loo as well as visit it either early in the morning or late at night, once again making you vulnerable.

We presented the data to the community and had a discussion around it. The women and girls decided to paint the walls of the toilet complex with messaging including the sections of the law that make it crime as well as engage with the young men and invite them to join the campaign. It had an immediate effect. The couch disappeared within the week, and the young men became advocates for change, not only joining the campaign but also educating their peers on appropriate behavior.

Ending violence against women and girls is important because it is critical for them to feel safe in public and private spaces. Further, in many low-income communities, young girls drop out of school because it is not safe for them. Under the guise of safety, their parents make them stay at home to “protect” them until they are ready for marriage which is often 15 or 16 years of age. Making public spaces safer is critical for a girl to get an education and then a career, leading to financial independence and the ability to explore her potential.

If we are able to achieve this, we can truly say we are creating a world where at least 50% of the population is not left behind.

To mark the 16 Days of Activism to end gender-based violence, the UN Foundation is featuring a diverse chorus of voices against violence through Human Rights Day, December 10. Visit the UN Foundation blog to learn more about the dimensions of this challenge, to read about unique and emerging approaches to end it, and to UNiTE to end violence against girls and women. Support the UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women here.

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts