As the UN agency responsible for assessing the science of climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has shaped our understanding of the existential threat of a warming world. Since its founding in 1988, the IPCC has produced a series of groundbreaking reports that support the scientific case for global climate action. And in 2018, the agency permanently changed the global conversation on climate change with its special report on the consequences of breaching the 1.5°C temperature target above preindustrial levels.

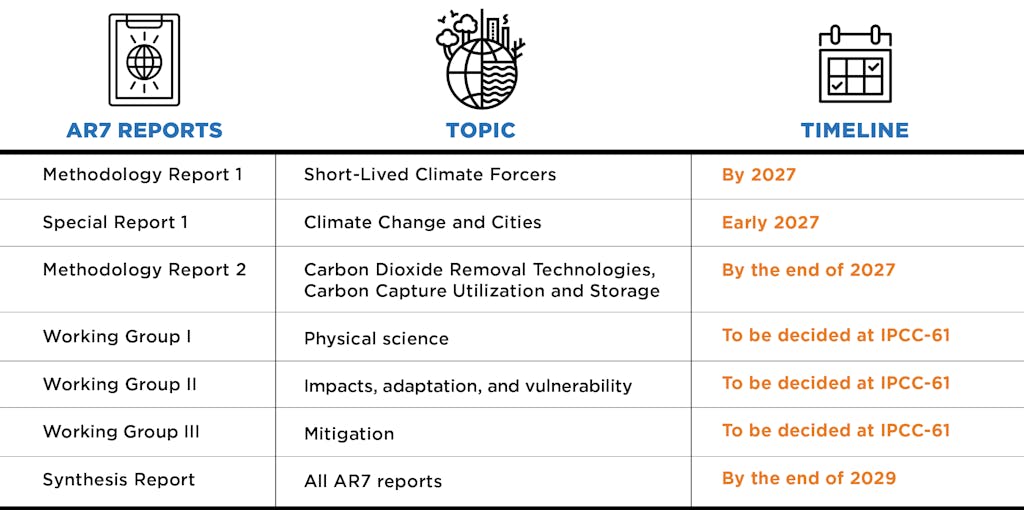

Delegates met in Istanbul, Türkiye for the Sixtieth Session of the Panel (IPCC-60) to decide on the report topics and timeline for its seventh assessment cycle (AR7). The newly elected Chair, Vice Chairs, and Co-Chairs, along with member governments and observer organizations, are applying lessons learned from the sixth assessment cycle that concluded in 2023, such as the increased likelihood of delay in report timelines and the need for further collaboration between teams.

“This cycle rests on the shoulders of previous cycles … building on both the achievements … and the important lessons we have learned,” IPCC Chair Jim Skea said in his opening remarks at IPCC-60. Looking ahead to AR7, he reiterated the IPCC’s commitment to “use the best available science to deliver focused, policy-relevant reports and provide timely and actionable information to policymakers,” and to “spare no effort to ensure a truly inclusive, diverse and representative IPCC” in pursuit of those aims.

Every Year Counts in Race to Reach Paris Agreement Goals

The IPCC took a decisive step away from business as usual by deciding that the final report in the cycle — the Synthesis Report — should be produced within five years, by the end of 2029, rather than the usual seven. That may not seem like much, but every year matters as we race to keep the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature target within reach. Those two years mean that one or two, if not all, of the three working group reports on the physical science of climate change, climate impacts, future risks, and adaptation and mitigation will be completed by the end of 2028.

As a result, the best available science will inform key UN processes that will ultimately shape how countries respond to global warming. For example, the reports produced during the cycle will inform the second Global Stocktake (GST-2) under the Paris Agreement, which provides a critical moment of self-assessment on where the world stands in the fight against climate change. “By aligning IPCC and GST activities and timelines we can spearhead climate ambition and action — a win for the planet,” Simon Stiell, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) explained. As the deadline for the 2030 Agenda arrives, the reports will also help leaders evaluate progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals in the final years of this decade.

“This body has, cycle by cycle, grown into the absolute authority on climate science,” said Inger Andersen, UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, during the opening of the IPCC-60. “However, as I see it, the seventh cycle may be the most important yet … providing the science to back the work that must be done.”