This spring, Graham Christensen witnessed the worst flooding of his life. Hundreds of farmers in Nebraska saw their fields submerged in as much as four feet of water. Nebraska’s governor said the natural disaster caused the most extensive damage in the state’s 152-year history. All told, the state’s agriculture industry suffered an estimated $1 billion in losses.

For Graham, the devastating floods are not only a harbinger of what awaits farmers in the future, but an urgent call-to-action. “Nobody’s seen nor experienced anything like this to our knowledge. Our ancestors claim they never have either,” Graham says. “Half of our state was pretty much underwater. It was really a shocker to know that this could happen in the middle of the country. We always figured the coastal folks were the ones in the most danger from climatic extremes.”

As a member of the National Farmers Union and a firm believer in the power of “regenerative agriculture” — an approach to farming and grazing that captures carbon in the soil while restoring soil biodiversity — Graham is advocating ways for farmers young and old to rethink how the nation grows its food. “There’s no way we’re going to reduce emissions unless agriculture is functioning as a huge part of the solution.”

Along with his brother, Graham is working to take over his parent’s corn and soybean farm. They’ve already installed solar panels that generate nearly all of the operation’s electricity, and he’s exploring new ways of farming in the areas above the first layer of crops to grow more food per acre while improving the farm’s soil.

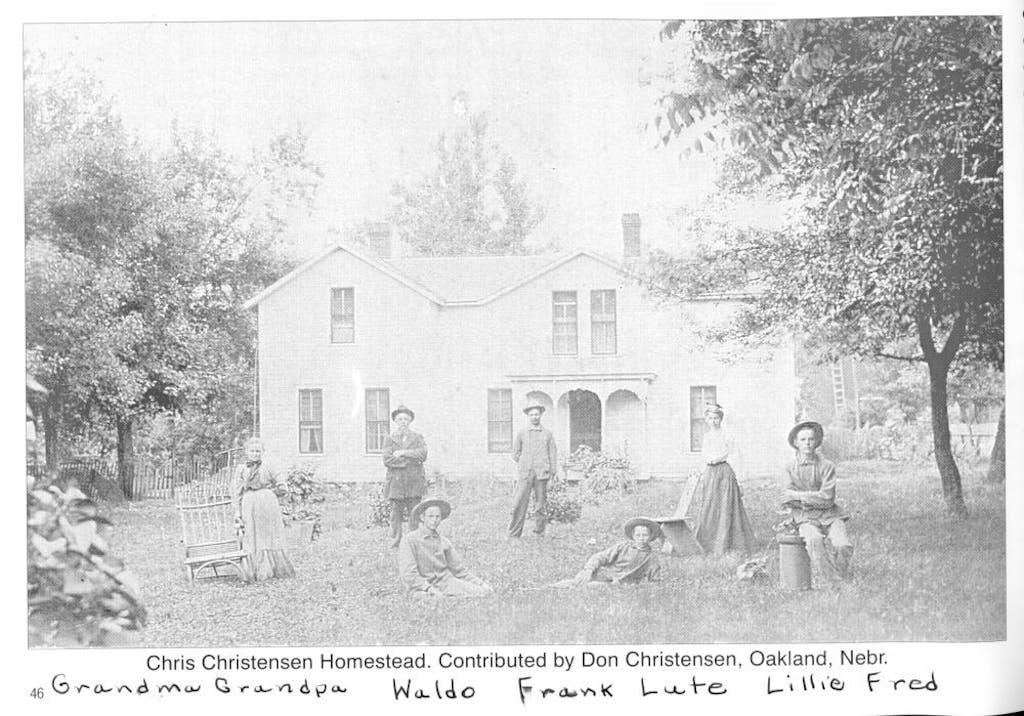

My brother and I are fifth-generation farmers. Right now we’re a fairly typical northeast Nebraska corn and soybean farm. However this is beginning to change again. On our farm, we’ve gone through all kinds of changes over its 150-plus years. We’re always changing and adapting to the times.

It’s definitely a time of transition for our farm. My father and my mother have been working hard to try to hand this farm down to my brother and me. I think it’s probably natural that we have slightly different visions for the future of the farm. We have a lot of kitchen table conversations trying to meet our goals as well as honor the fact that this is a business and we can’t take the operation backwards if we’re to keep this farm in the family for another 150 years.

My great-great granddad settled here. He left Denmark because he felt oppressed. In his U.S. residency papers, he said, “It is bona fide my intention to become a citizen of the United States, and to renounce and abjure forever all allegiance and fidelity to all and any foreign Prince, Potentate, State, and Sovereignty whatever, and particularly to the King of Denmark of whom I was a subject.”

Looking back to my ancestors and why they fled Denmark, I think maybe we’re not succumbing to a king or a queen here, but we’re at the mercy of massive corporations now. The concentration at the top with companies like Costco and Walmart trying to own every profitable sector in the ag industry, and the level of concentration in the chemical companies are making no marketplace look competitive, transparent, or even acceptable for farmers.

It’s getting ugly really fast here. We’re at a breaking point. We’re seeing a concerted effort to remove family farms and produce cheap food of less nutritious quality. If you just took a view of the horizon here, you’d see acres and acres of one crop grown across this whole area. This approach is not working. It’s not working for the public’s health. It’s not working for the soil. It’s not working for the air or the water either. And it’s definitely not working for young people who want to farm.

That’s why we formed our own organization — RegeNErate Nebraska, which is advocating for an across-the-board approach to regenerative agriculture.

Ultimately, as far as the climate situation goes, there’s no way we’re going to reduce emissions unless agriculture is functioning in a way that is a huge part of the solution. In fact, agriculture may give us our only chance to actually draw CO2 down again and recapture all of this excess carbon. There’s massive potential here. We’re not the only farm that’s talking about this either.

The solution is in the soil. One way we can draw additional carbon down is through no-till farming. On our corn and soybean farm, the plants breathe in CO2, exhale oxygen, then store the carbon underground continuously every year that there’s growth. And if you don’t till the land, you don’t break up all this carbon in the ground like we did during the Industrial Age — when we plowed everything up in these big vast prairies and all of that underground carbon was released into the atmosphere. Soil health has been our way to resonate with farmers without having to get into the absurd politics that have formed around the term ‘climate change.’

Cover cropping is a vital step towards building soil organic matter and reducing emissions. On our farm last year, we grew a shorter season of soybean and harvested earlier. Then, we drilled in oats as a cover crop. With sun and a little bit of rain, the oats sprouted up and they started breathing in carbon and taking it back down into the ground, which pulls additional carbon into the ground than what is typical in most modern midwestern conventional farming systems. In past years, we would not have added cover and that means that we were not pulling additional carbon out of the atmosphere and into the ground. When all of the flooding happened this spring, we were able to show my dad that this approach could hold topsoil in place and slow soil erosion. Those roots from the oats were enough to hold some of our soil in place despite all of rainfall that came in such a short period of time.

When adding cover cropping like this, it also becomes easier to return livestock back to the land on tillable acres. Cattle can start to graze cover crops like oats or other cover crops in well-managed rotational cycles that closely mimic bison movement across the prairie back in the day. That’s what we’re trying to get back to — because that’s when organic matter in the soil was at its highest. It was a natural process. These bison were helping fertilize the soil. And by reintroducing livestock grazing across the majority of the land, we’re able to cut down on most of our reliance on synthetic nutrients within only a handful of years.

Improved grazing techniques, and getting away from massive confinement systems called Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), also give us a better chance to reduce methane and nitrous oxide emissions. In CAFOs, livestock create huge pockets of methane and a lot of the animal waste does not absorb into the ground as fertilizer but rather runs off. Not only does this put water resources and therefore the public’s health at risk, this also means that much of the benefits of manure are wasted or heavily concentrated into areas that are not able to properly break down the highly nutritious fertilizer.

Not only do the chances of excess methane emissions increase, so do nitrous oxide emissions as more farmers turn to synthetic nutrients to fertilize their crops instead of relying on livestock as was the tradition in the past. There is also some evidence that eating corn-based diets can create higher methane discharge than a grass-based diets as well.

So now with added cover and livestock re-introduced to the soil, you’re not only tackling CO2 with more roots in the ground, but you’re also tackling rising methane and nitrous oxide emissions, which are both more harmful greenhouse gases than CO2.

Then you can take it one step further and start adding agri-forestry to the farm — trees that produce fruits, nuts, or berries — and put them in between your rows of corn and soybeans with livestock grazing through. This reduces greenhouse gases even more and creates more fertility and resiliency in the soil, and more prosperity for the farmer. This is a win-win-win!

Wind and solar in rural areas can also provide big benefits for our communities and be a part of the climate solution. We’re really excited that our farm has been able to become mostly energy independent with solar energy.

If you implement all of these things, there’s way more diversity and marketplace opportunities for the farmer, and there’s also way more food produced per acre. Utilizing these techniques mean we can also cut out some of the input expenses we’re paying now by working hand in hand with mother nature. That’s why regenerative agriculture is so powerful.

It really is encouraging right now to see so many farmers asking questions about regenerative farming and seeing newly invigorated young people who are finding the path back to agriculture. It’s just a no-brainer. We’re united in this. Once again, the politicians can make this a political issue, but there is a lot of momentum out here and it’s growing.

Now we just need to get consumers to rally around regenerative farmers and ranchers and demand more than what’s just in the nearest supermarket. When the consumer begins to understand that what they are currently consuming has most likely been sitting around soaking in manure and pumped with chemicals I guarantee they will respond by supporting ethical farm businesses. Knowing who your farmers are — that’s the mentality we have to get back to.

With rural areas now more depopulated than ever, urban food consumers have all the power in repairing our broken system. That’s why we need urban-rural unification, With the technology, we have now — with apps and social media — consumers now have the ability to have complete transparency and connection with us again, even though they may be in New York or California and I may be in Nebraska.

I turn 40 in November, so a lot of things have changed over my lifetime. We just don’t have a lot of independent family farmers anymore. I graduated high school with 40 people in my class and only three of us that I’m aware of actually farm.

Now more than ever we need a new wave of young farmers. The average age of the farmer is 57. So you have the baby boomer generation retiring and over the next 20 years they will turn over a tremendous amount of the land. We must ask ourselves what’s going to happen to that land? We have to be able to find ways to transition that land to the next generation. So that’s going to be a focal point of our next conversations. Otherwise, it’s going to be owned by foreign governments and massive industrial corporations.If that happens, it’ll be game over for the climate.

I have great confidence that this is not our destiny, and I truly believe we will get this ship turned around, but unless we’re all in this together and have a very basic understanding of how all of this is connected, we’re going to be in big trouble.

We don’t have to be the last generation of family farmers, but rather the beginning of a new chapter in agriculture. As we unify together around highly nutritious, regenerative foods we will find that we truly do control our own destiny, and furthermore we will be looked back in history as heroes on the front lines working together on the solution to climate change…the solution which can only be found in the soil.