Despite progress on many global development issues in recent decades, two destructive trends are on the rise – severe hunger and conflict/fragility – and it’s not by coincidence.

Last week the 2018 Global Report on Food Crises was released. This third-edition report, prepared collectively by a dozen leading global and regional institutions including the European Union, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the United Nations World Food Program (WFP), aims to both elevate the importance of the issue and increase the ambition and urgency of action around ending hunger and reducing human suffering.

A stark finding that is coming into sharp focus is that conflict and insecurity are the primary culprits behind food insecurity in 18 countries, accounting for 60 percent of the global total. The number of food-insecure people needing urgent humanitarian action is growing and in nearly all regions. Climate disasters, such as droughts, are also a main driver, often occurring simultaneously with conflict in several African countries, including Nigeria, Somalia, and Sudan.

In fact, the UN estimates that 80 percent of its humanitarian funding needs are due to conflict. By uncovering the connections among conflict, climate, and hunger, the report reveals the true value of prioritizing and addressing fragility and sustaining peace. Conflict and insecurity, which can be triggered by hunger and climate disasters, cause more instability by disrupting food production and driving displacement.

Once this vicious cycle gains momentum, humanitarian agencies face challenges stopping it. As conflict-affected regions become increasingly inaccessible and/or besieged by violence, vital supplies and services often cannot be delivered to the most vulnerable. The effects of insecurity and fragility are compounding. As more people suffer from hunger and critical infrastructure for health care and sanitation collapses, disease and infection spread, leading to more malnutrition. This was exactly the case in 2017 in both Yemen and South Sudan, both of which experienced severe outbreaks of cholera due to protracted conflict and a breakdown in essential services.

The report predicts that conflict and insecurity will continue to be the primary drivers of food security crises in 2018, affecting Afghanistan, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, north-east Nigeria and the Lake Chad region, South Sudan, Syria, Yemen, Libya, Mali, and Niger. New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof just recently reported from the Central African Republic to drive desperately needed attention to the conflict-poverty nexus in the world’s hungriest country. Yemen, another country on the precipice of collapse as it enters the fourth year of a civil war, is predicted to face the largest food crisis in 2018.

The impact of severe dry weather on crop and livestock production is likely to heighten food insecurity throughout parts of East and West Africa, and in southern Africa. While the situation is forecast to be better than last year due to increased levels of cereal production and falling food prices, increased investments will be needed to ensure that vulnerable populations can build resilience to and recover more quickly from future climate shocks.

Treating the symptoms of food insecurity will not be enough to reverse these trends. In a briefing to the UN Security Council last week, Mark Lowcock, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator with the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), urged action, stressing that peace and political solutions are vital to disrupting the vicious cycle of conflict and hunger. Countering continuing crises will require a re-commitment to political solutions for sustained peace.

Similarly, earlier and longer-term interventions, such as investments in agriculture and climate resilience, will be crucial to preventing crises that spill across borders and spiral beyond control. The close coordination among UN agencies, such as WFP, OCHA, and UNHCR working in-country, coupled with the financial support of the entire international community, is an important defense and mechanism for putting prevention at the heart of development – as outlined by recommendations in the recent joint UN-World Bank “Pathways to Peace” report. And the UN will hold a High-Level Meeting on Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace next month to continue to elevate the importance of prevention and peace.

Continued focus and accountability on prevention will be key to mobilizing the solutions needed to address the growing connections between conflict and hunger. As WFP Executive Director David Beasley explained, “if we bring together political will and today’s technology, we can have a world that’s more peaceful, more stable and where hunger becomes a thing of the past.” Let’s hope that this report, and others like it, will help to foster more innovative and scalable solutions to peace, development, and food security. We need to act with urgency to stem the tide of this worsening crisis before it’s too late. The 124 million people experiencing food insecurity in conflict zones don’t have time to spare.

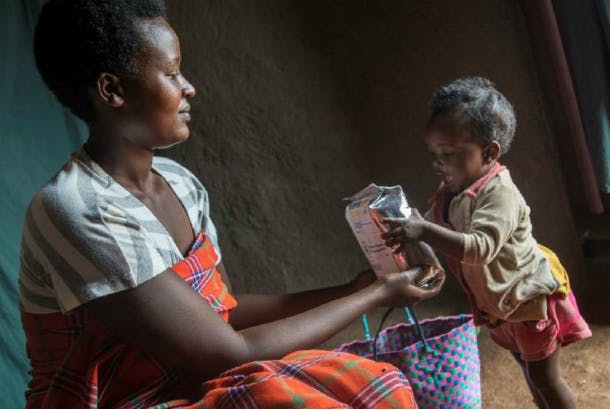

Photo: WFP/Rein Skullerud

View All Blog Posts

View All Blog Posts